Rana Foroohar’s strange case for raising interest rates. Does stringent monetary policy really produce equality?

.

Miss the New Notes on the Crises podcast? Check out episode one with Joe Weisenthal. I am also excited to announce today that I am doing an end-of-year sale. From now until the end of the year, annual subscriptions are 50% off. That means that for less than 5 dollars a month you can get a subscription to both the Notes on the Crises newsletter and podcast.

Subscribe

For some time now, centrist and outright right wing pundits have begun to repackage “hard money” arguments as arguments against increasing inequality. Where once raising interest rates was necessary because the economy was overstimulated or labor was too rowdy, now we must raise interest rates because low interest rates are causing too much inequality. The conclusions are the same, but the arguments have been repackaged for a more class-conscious age.

I have been looking for good opportunities to write about this which came in the form of a particularly straightforward and troubling Financial Times op ed from Rana Foroohar entitled “The left’s low-rate fantasy makes inequality worse”. The main through line of the article is the claim that low interest rates cause bubbles which increase inequality while playing down the effect tighter monetary policy would have on wage growth and employment at the low end of the labor force. Playing up the former while playing down the latter paints the benefits of low interest rates as “too costly”.

The article throws out a number of justifications for this view. One particularly confusing line points to “academic research” showing low interest rates cause asset bubbles but links to a theoretical paper on the natural rate of interest and inequality which doesn’t discuss bubbles. This is the only real justification for the assertion in the article. Plenty of debt fueled bouts of asset price increases have continued amid high interest rates and rising interest rates. Meanwhile, Federal Reserve interest rate hikes from August 2004 to August 2006 did little to cool the U.S. housing market. That’s no surprise when banks were systematically committing fraud in order to gain double digit returns. How high does Foroohar want the U.S. to raise interest rates?

This question becomes particularly urgent since she implies that she wants the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates in order to crash the cryptocurrency market:

With stock prices still near record highs, and US home prices up nearly 20 per cent annually, it’s no wonder that small-time investors are desperate for their slice of the pie. Income growth won’t buy you a house. And yet, risk is greatest just when the punchbowl is about to be pulled. I worry about the rise of retail speculation on apps such as Robinhood. I also worry that investors with fewer liquid assets are those taking on some of the biggest risks. Consider a recent Harris poll showing that 15 per cent of Latino Americans and 25 per cent of African Americans say they’ve purchased non-fungible tokens, compared with just 8 per cent of white Americans.

First, it must be emphasized that taking this Harris poll at face value strains credulity past its breaking point. There is simply no way that 1 in 4 Black people own an NFT and that the proportion of Black people who own an NFT is triple the proportion of white people who do. If you look at the actual poll it helpfully informs closer readers that: “[t]his online survey is not based on a probability sample and therefore no estimate of theoretical sampling error can be calculated. Figures for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, region and household income were weighted where necessary to bring them into line with their actual proportions in the population.” In other words, there isn’t a margin for error- there’s a chasm of possible error. It is painfully obvious that crypto fans who responded to an online poll mentioning crypto and “non-response bias” from non-cryptocurrency holders blew up the results.

The misuse of this poll in this argument is however, in some sense, a distraction. The more fundamental problem here is the idea that raising interest rates to 4 or 5 percent will kill interest in cryptocurrencies, a space which has seen extreme levels of volatility and returns. Someone who hears tell of bitcoin purchased for a few dollars and sold for fifty thousand will not be disuaded by a few percent higher interest rates. If regulators have consumer protection concerns about investments in cryptocurrency, they should use regulatory tools to combat them. If regulators see a “bubble” and want to discourage monetary flows into cryptocurrencies, they have tools to do that too. The idea that the macroeconomy should be managed with an eye to cryptocurrency prices is even more absurd than the suggestions of yesteryear to manage the macroeconomy with an eye to housing prices.

Leaving the “bubble” argument aside, there is still the question of wage and employment growth. Rana doesn’t give much hint of her perspective of us in the article. She tells us that the Fed’s limited interest rate hikes in 2015 and 2016 didn’t have much of an effect on wage growth. But those hikes were small, quickly stopped and happened after wage growth among the lowest quarter of workers began to accelerate. She also tells us that lowering rates doesn’t increase employment much or accelerate low wage growth very much. Even if that were true, it doesn’t follow that raising interest rates couldn’t have a bigger negative impact. I have argued in the past that the effect of interest rate changes are asymmetric.

Her perspective makes more sense when readers realize that she thinks recessions, unemployment and slowing wage growth for marginalized workers is inevitable. It just is a matter of happening now, or happening in bigger and worse ways in the future. She links to a remarkable article she wrote in 2019 bemoaning the lack of recession since the Great Financial Crisis. In it, she states that:

All this begs the question of whether longer really is better when it comes to business cycles. Recessions are a natural and normal part of capitalism, not something to be avoided at all costs. Indeed, the Deutsche Bank economists argue that productivity would be higher and American entrepreneurial zeal stronger if the US business cycle had not been artificially prolonged by monetary policy.

It’s important to remember that, as I pointed out in one of my very earliest pieces for Notes on the Crises in March of 2020, the economic recovery since the Great Financial Crisis had died of a pandemic, not of old age. A recession wasn’t otherwise inevitable. It is only made inevitable by policymakers who take a complacent view to recessions, encouraged by pundits like Foroohar. Later on last year I also criticized the fallacies baked into the Deutsche Bank view she recounts.

Whatever the facts may be, Rana’s view is now clear. She doesn’t think macroeconomic policy can sustain recoveries which lead to tightening labor markets, so why bother trying? The attempts to try “just” cause bubbles which increase inequality and make things worse. It’s notable that she avoids talking about the fiscal policy interventions last year which sustained incomes for very many ordinary workers, actually leading to much more income protection for lower wage workers than the Great Financial Crisis. It is, of course, the amazing and unprecedented response of fiscal policy which has sustained overall income growth and made it possible for austerity-leaning pundits to make a case for contractionary policy at all.

Of course, there is a grain of truth in the argument that there is some sort of connection between low rates and wealth inequality. Future income streams, whether potential or actual, are frequently turned into forms of property that can be bought and sold now. Rental housing is bought and sold today incorporating the value of rents that can be charged decades into the future. Bonds, stocks, real estate properties and other such assets will see their valuations rise when interest rates fall according to the rules of standard valuation methodologies.

However, there is less here than meets the eye. For one thing, capital gains come from falling interest rates, not low interest rates. Sustaining the same interest rate stance doesn’t have the effect of increasing capital gains, and certainly not to the extent that actually lowering interest rates does. This sort of capital gains happened in the 1980s when rates were falling from 20+% to “merely” 7% or so. Holding interest rates at the same level shouldn’t be conflated with this interest rate effect. Further, from an inequality point of view, the high returns provided by such high interest rates is as relevant as these capital gains. It's not hard to get rich when you are earning your principal back in just a few years.

By definition, the total return from a bond is the interest received plus any possible capital gains from selling the bond. When interest rates fall, future bonds provide less interest at that rate level. They also provide less scope for capital gains than the “incumbent” bonds. Meanwhile, the current holders of those bonds won’t see any difference in return as a result of these paper capital gains unless they sell those bonds. The result of all this is that high bond returns are ultimately sourced to high interest rates, whether currently or significantly in the past. The decades long “bull market” in bonds is made up of already high returns from high interest rates getting “supercharged” by their dramatic decline (bond investors and analysts distinguish between different types of capital gains to strategize the returns “bond funds” provide. That is beyond the scope of my analysis here, though this thread is a good starting point)

The point is that when commentators are quick to blame bond returns on historically low interest rates, they ignore the other side of the coin- high interest rates in the past. Why should we increase future bond returns (not to mention loan returns) by making it easier to charge higher interest rates in the future? Or set the stage for a future “bull bond market” where interest rates can again be lowered? A low and flat yield curve will decrease bond market returns over time, if that truly is our goal.

By this point a reader may be saying “okay, that may be true about bonds, but what about stocks and real estate?” This is an important question. It is also more complex. Bond returns (whether capital gains or interest) are mainly about interest rate valuations. These other assets experience returns that are, for the most part, unrelated to interest rate valuations. Interest rates can be at zero, but a stock can still experience big capital gains simply because the company grows substantially, paying more dividends and/or accumulating more assets (thus supporting stock price increases). In fact, this is one of the main reasons to invest in stocks in the first place and why the concept of an “expensive stock” is relative. A very expensive stock can still provide high returns if it will indeed keep on growing.

The flipside of these points is that if interest rate valuations are much less important to returns in these areas, they are much less relevant to the impact returns to these assets have on overall inequality. In that portion of returns for which interest rate valuations are relevant, the tradeoff between capital gains now and yield in the future remains just as relevant here as they do for bonds. More than anything, this viewpoint emphasizes how ephemeral interest rates are to wealth inequality as an ongoing and intergenerational process- which makes sense. Once stated, it becomes obvious that owning all the companies and all the real estate would generate most wealth inequality and most increases in measured wealth inequality.

This all leaves us with the idea that lowering interest rates today can raise measured inequality today through increasing the current value of future yields, but it is not an enduring effect and becomes swamped by lower yields over time. More than anything else, we’ve clarified that interest rate valuations are a sideshow to the story of U.S wealth inequality. Targeting the wealthy’s returns will require some combination of regulation, reallocating coordination rights, democratizing companies and heavy taxation. It shouldn’t shock readers that such a policy program is not espoused by monetary policy hawks who cry over interest rate driven inequality.

This logic appears even more broken when put in a comparative context. As economist JW Mason pointed out many years ago, the U.S. has more assets which see paper price increases because more of society’s wealth is converted into property which can be freely bought and sold. Countries like Germany have lower stock valuations because of worker representation and influence on companies and a higher proportion of renters. Those renters have strong legal protections for their tenancy which decreases measured real estate values. If we followed the logic that interest rate policy should be made with these valuation changes in mind, the very fact that the U.S. is a substantively more unequal society would push towards the U.S. raising interest rates to paper over that fact while countries like Germany could “afford” to have lower interest rates.

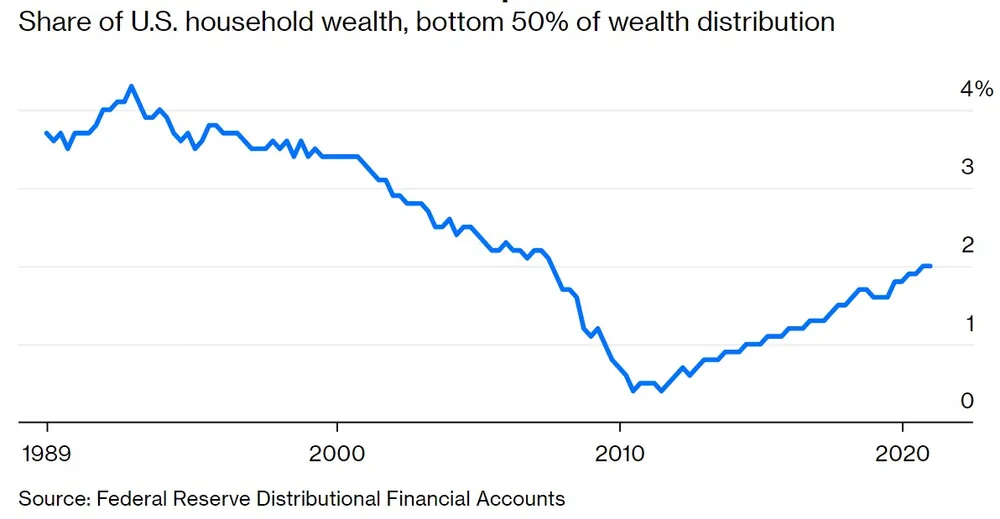

This doesn’t provide any coherent guide to policy. One final issue is important to talk about. Throughout the article, Foroohar implies that higher interest rates would lead less wealthy households to build wealth, closing wealth gaps while negative “real” interest rates increase wealth inequality through discouraging wealth building. This is false. The bottom 50% of households in wealth are net debtors and their net-worth is at 2% of overall net-worth, a post-GFC high. Higher interest rates will drain their disposable income, lessening any possibility to build wealth. After all, paying off debts is a form of wealth building as well.

In fact, as economists Sandy Darity and Darrick Hamilton constantly point out, saving doesn’t have much to do with wealth building at all. It is inherited wealth which drives household wealth inequality. This is obvious once we remember that all the companies in existence have associated owners or shareholders and the vast majority of urban and suburban real estate is already owned by households. How could wealth be anything other than made up of these intergenerational transfers? The children of Logan Roy in the HBO show Succession didn’t save their way to being heirs of an empire.

For all the attempts to dress themselves in the concerns of racial and social justice, these sorts of arguments appear stilted. Commentators like Foroohar are missing the spirit which drives concerns with inequality below the pundit class. No one cares much about some property claim somewhere going up in value in and of itself. What they care about is the power that that property can hold over them. They care about their inability to gain an income, live in good housing or improve their working conditions. They are concerned about the power a boss, landlord or creditor has over them.

Raising interest rates to cause a recession will hurt very real people. It will give creditors greater power over ordinary households and it will threaten the wage growth that lower wage workers have been experiencing. None of the people hurt by these policies will take much comfort in a graph that shows some billionaires experienced some paper losses while still having the power and control they have over the companies they operate or society at large. Raising interest rates to reduce wealth inequality is the equalizer of knaves and fools.

Printer Friendly Version

Subscribe

Subscribe to Notes on the Crises

Get the latest pieces delivered right to your inbox