Banks as Payment Plumbing Monetary Policy 101

What the Behind-the-Scenes Details Tell Us About Money

#MonetaryPolicy101 is a weekly series about the basics of monetary policy. This is the sixth Post. See Post 1 here, Post 2 here, Post 3 here, Post 4 here and Post 5 here. If you like this series please consider taking out a paid subscription here. It is reader support which sustains my ability to treat this substack as a full time job.

So far in this series I’ve focused on clearing payments between individuals and between individuals and businesses. This is important but it is only the “retail” segment of the payments system. The more critical and complex part of the payments system is the “wholesale” part- that is payments between financial institutions, the central bank and the government. This is commonly referred to as the “plumbing” of the financial system because it isn’t apparent to the retail user, makes the entire system function and can get “clogged”, causing problems everywhere. Most of the more technical aspects of the financial system that experts focus on are problems and quirks embedded in the payments system plumbing. Nonetheless, understanding the basics of payment plumbing is important to grasping the nature of money itself.

The first thing to understand about payment system plumbing is that it is all about clearing and settling payments. Millions of discrete payments running into the 100s of trillions of dollars runs through the U.S. dollar payments system everyday. Making a discrete payment for each and every one of these transactions would be extremely cumbersome, so instead payments systems tend to “net out” transactions at the end of some period (a day, a week, and, sometimes, even longer) and only require a payment for the net amount owed. It’s important to grasp what “net settlement” (as opposed to “gross” settlement) means. At a fundamental level it means that in between settlement times, financial institutions are providing each other credit. They are a creditor for extremely large sums worth of transactions while at the same time being debtors for another set of offsetting transactions. Providing credit inherently means taking on credit risk. On the other hand, it also makes the payments system far more flexible.

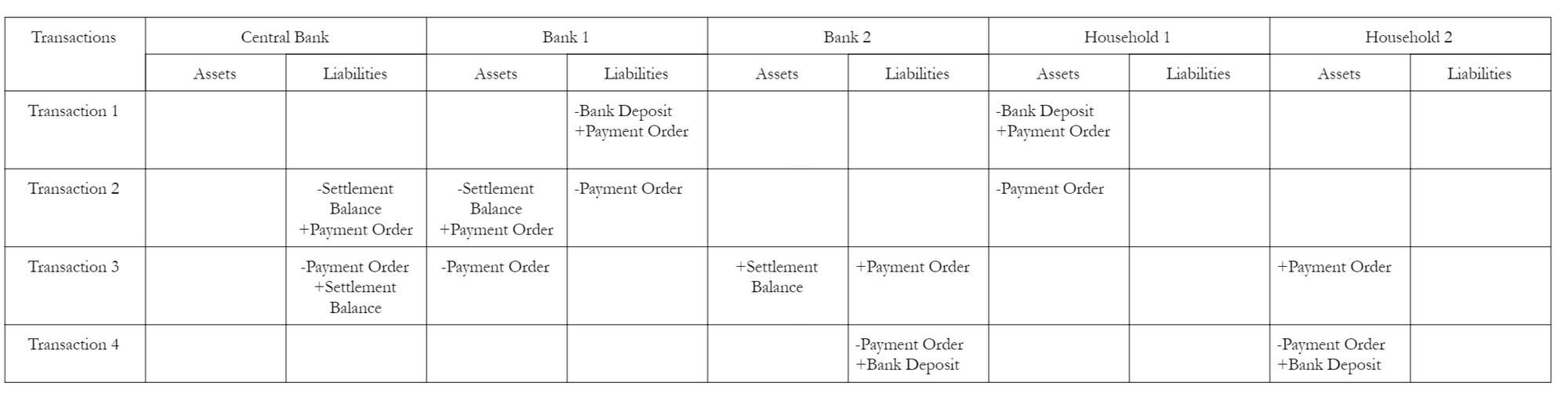

This brings me to what I think is a critical but often overlooked issue- how do financial institutions make payments to each other? The easy and obvious answer is the IOU of a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve. Specifically, settlement balances in an account that banks have with the central bank. I’m going to run through a set of those transactions to remind readers of how this works. Normally I run through these transactions as all one smooth step for simplicity, but processing a payment is actually a series of steps. As the reader will see below the first step is that Household 1 initiates a transaction which debits their account and creates a payment order. The second step is that their bank, Bank 1, recognizes this and sends a payment which debits their own account with the Central Bank and creates a payment order for the Central Bank. The Central Bank recognizes this payment order and credits Bank 2’s account, generating a payment order to the credit of Household 2. Finally, that payment order is recognized and Bank 2 credits Household 2’s bank account.

From this set of transactions, it's clear that settlement balances in a settlement balance account with the Central Bank were used to make payments between banks. However, the reason this is the case is I set up the series of transactions to work that way. In bank payment systems, especially historically, payments are usually settled on a net basis as described above. What’s important theoretically about this idea is that it means most payments were and are not settled with a final settlement asset like a central bank IOU. Instead, most settlement happens conditionally with a conditional settlement asset. The critical legal difference between these two types of instrument is that one is legally established to make payment final on delivery no matter what, while conditional settlement assets are acceptable in payment for conditional reasons. The most obvious conditional settlement asset is a check ordering one bank to pay another on behalf of its customer. The bank receiving the check would have discretion to accept it or not if it were the check of a third party bank.

The bank receiving the check may even have discretion to not accept its own check as payment and demand payment in a final settlement asset while the check is processed and cleared more slowly. These kinds of aggressive actions fill banking histories. Take, for example, this story of the famous Suffolk Bank in the 1820s:

When the Lincoln Bank of Wiscasset, Maine was asked to redeem $3,000 of its notes, it first tendered a Boston [bank] draft that the Suffolk's agent promptly refused, asserting the Lincoln Bank's legal obligation to redeem in specie. The Lincoln's cashier then delayed redemption by methodically counting out small coins. The South Royalton Bank of Vermont informed the Suffolk's agent that it would begin by redeeming its $1 notes. By the time this was done the closing hour was reached. Overnight the South Royalton obtained specie from two neighboring banks and the following day, when the Suffolk's agent reappeared, the bank's cashier announced that he stood ready to redeem its $2 notes. Even while these events unfolded, the South Royalton's attorney filed suit against the Suffolk charging it with a “malicious intent to break the Bank without cause”.

These kinds of incidents are extraordinary. Most of the time, conditional settlement assets are acceptable forms of payment. Since they are usually acceptable and net clearing is far more convenient than proffering a final settlement asset each and every time a payment needs to be made, most of the time final settlement assets are a secondary form of settlement, even as their existence is critical. In fact, banks would certainly ideally like to never have to make or receive net payments at all which means clearing and settlement would happen exclusively with conditional settlement assets. Another way of thinking about these two types of settlement assets is to treat “conditional settlement assets” as “inside money” and final settlement assets as “outside money”. One is produced through the course of making and receiving payments between banks while final settlement assets come from “outside” the banking system. Historically these included gold and silver coins from mints and clearinghouse certificates. Today, the main final settlement assets are central bank settlement balances, with perhaps a place for treasury-issued media in certain times or places.

It may feel like I’ve spent far too much time on these intricate points about the plumbing of the banking system. Readers may be asking “what’s the point?” This is all important because it dispels the myth that credit, especially bank credit, is merely a “fake” or “fictitious” claim on “real money”, whether the person making the claim means settlement balances held with a central bank or gold and silver. What this post illustrates is that the plumbing of the banking system can be organized in countless ways, with many different types of settlement assets and different balances between final settlement assets and conditional settlement assets. All these details are irrelevant to the retail user of the payments system. What’s valuable about a bank deposit, or a bank note, is that it can be used to make a payment to another individual, a financial institution or the government. Retail users don’t care how it happens, as long as it happens. Bank money is not some fake veil over “real money”, it is money to us because the payment infrastructure itself is “money” to us. As Joseph Sommer, Legal Counsel to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York says, "Money is what payment systems do".

It’s worth quoting Sommer some more:

In other words, a bank liability is nothing more than the right to go to court and obtain a judgment against the bank for damages. It is not a property right to specific bank assets; rather, it is a contract right to a judgment for money [...]For our purpose, "payment" is the result of extinguishing a bank liability. Because the bank liabilities are seldom extinguished by the execution of a judgment, a payment is best viewed as a settlement of the customer's right to collect a judgment from the bank on the liability. This definition is not strained: It is what banks do

For our purposes, what’s critical about what Sommer is saying is that if a bank deposit isn’t a property right over specific bank assets, it can’t be a property right over specific final settlement assets either. A bank’s liabilities may become demonetized because of payment system failures or a general banking crisis, but that doesn’t mean they were never money to begin with. As long as the payments plumbing is functioning well and clearing payments, the bank liabilities that retail users of a bank payments system interact with are money. In my experience this is one of the most difficult concepts to understand in monetary theory. It’s worth spending some time really thinking deeply about this point and reflecting on one’s own daily life. Next week, we’ll spend some more time examining why banks are special.

Subscribe to Notes on the Crises

Get the latest pieces delivered right to your inbox