There Are No Simple Answers in the “Greedflation” Debate: A Response to Economist Marc Lavoie

Long time and close readers of Notes on the Crises will be aware that I’m a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) scholar. More than three years ago now I published written remarks of a talk I gave to a Federal Credit Union which laid out my (brief) articulation of some of MMT’s core ideas, and how those insights related to the then-raging Coronavirus Depression. Nevertheless, I tend not to write about MMT explicitly for Notes on the Crises. Nor have I written about theoretical debates among non-mainstream economists more generally in this newsletter. I have usually sought out other publications to do that kind of writing.

However, I am now under contract with Viking Press to write my book on the Federal Reserve Picking Losers. As a result, readers can expect some more writing on these sorts of disagreements in this newsletter. Furthermore, having reflected on doing this kind of writing, I’ve come to the conclusion that readers will get more out of it than I’ve sometimes thought in the past.

One of my most popular pieces in 2020 was my explanation of the Kalecki-Levy profits equation and the logic behind it. People read me to get a different perspective and the best way to learn about other perspectives is to watch debates between people who disagree in good faith. You can’t learn all you have to know about from reading people express their opinions in the abstract. Dispute is key for clarification. Many of these debates also have much wider relevance than their theoretical terms might suggest.

Which brings me to the topic of today’s piece. Readers are aware by now that there is a big debate over the extent to which price increases over the past three years are driven by “profits”. I find myself being a strange sort of “moderate” in this debate. As I wrote about in July 2022, following the Kalecki-Levy profits equation, I don’t think a rise in measured profits by definition tells us that there are target profit margin driven price increases going on. To quickly remind readers, target profit margins are the expected (or “planned”) profits from selling a specific product for a specific price. These “expected” profit margins may not be realized — that is, actual profit margins can diverge from target profit margins for various reasons. Those reasons can explain why overall profits rise. A rise in measured profits “after the fact” does not ipso facto mean an increase in target profit margins at the product level nor that higher profit margins were specifically associated with price increases. What is often called “average profit margins” are in reality actual or “realized” profits. Those are divided by the total revenue from sales over an entire company, industry or even all nonfinancial corporations.

On the other hand, by that same metric, I also don’t think that a rise in aggregate profit explicable in macroeconomic terms definitionally rules out a relevant role for target profit margin driven price increases. That is an unsatisfying answer for all concerned, I know! But I simply do not think we have enough evidence to know what proportion of price increases (or price index growth) are explained by administrative decisions to raise target profit margins (and thus prices.) We certainly do not know in real time what proportion is driven by these various factors.

(By happenstance, I am about to run a workshop on the Kalecki Profits Equation and “Greedflation” in Poznan, Poland tomorrow.)

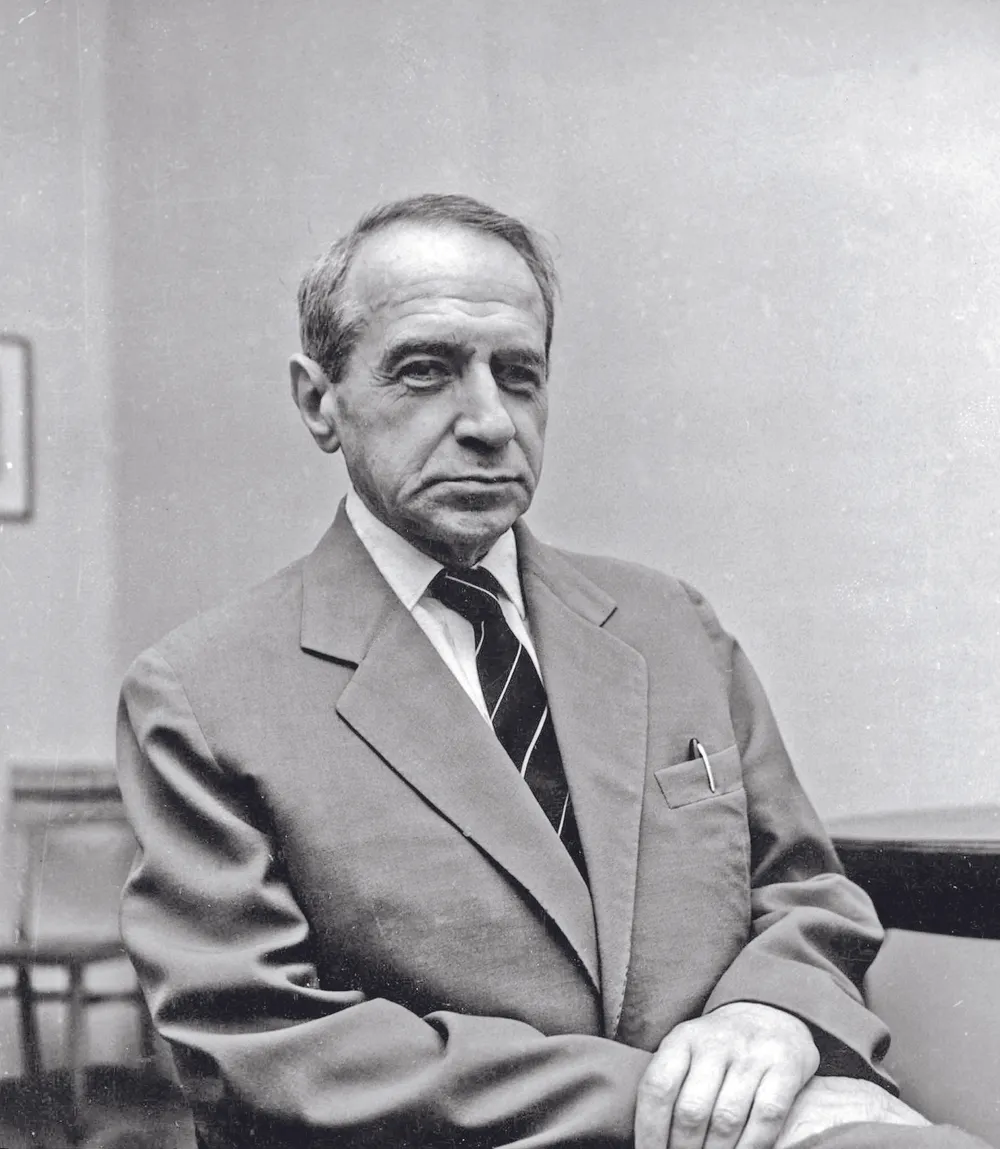

This past May another contribution to the debate over profits and covid inflation was provided by Post-Keynesian economist Marc Lavoie in a straightforwardly titled piece “Some controversies in the causes of the post-pandemic inflation”. Marc Lavoie is a very important figure in Post-Keynesian economics, having written the most read and utilized guide to Post-Keynesian economics, and co-writing the best known macroeconomic modeling textbook. His work is profoundly important in a variety of different ways and his modeling work alongside the late Wynne Godley takes the principle provided by the Kalecki-Levy Profits equation — to always make sure your economic narratives are accounting consistent — to new heights. This type of modeling, going under the phrase Stock Flow Consistent Modeling — is essential. This modeling approach seeks to carefully trace where financial (and physical) flows come from and go to in order to eliminate any possible “black holes” in the model. Check out. For example, this paper on modeling “open economies” in an accounting consistent manner. The point is that when professor Lavoie writes, a lot of people rightfully pay attention.

Having paid attention however, I find Lavoie’s piece puzzling. The true crux of his argument seems to be summed up in this quote:

[T]he rise in profits and the profit share can be explained without resorting to an explanation based on firms taking advantage of the situation and raising markup rates. In other words, this third explanation denies the generalized existence of profit inflation.

In other words, because we can provide a plausible explanation of higher profits without target profit margin driven price increases, we should. Why we should act this way is left unexplained. As I’ve written about previously, there are certain reasons to doubt parts of the “profit inflation” story. But the ultimate determining factor should be qualitative and quantitative empirical evidence —not our beliefs about what theoretical stories we should (or should not) “resort to”.

It’s also unclear what role the phrase “generalized” is playing in: “generalized existence of profits inflation”. Since the story he is contending with is a story about firm pricing decisions, the question of how “generalized” target profit margin driven price increases are is a sideshow. For the purposes of our argument, generalization is neither here nor there. All that matters is how significantly it contributes to CPI growth and particular sectors can drive the behavior of the whole index (as I’ve commented on in the past.) Most significantly, rental housing clearly sees profit driven, rather than cost driven, price increases. As a result, rising rents have been a very large part of “covid inflation”. Indeed, shelter price index growth “explains” (in an accounting decomposition sense) the continued elevated growth in CPI, a return to the pre-pandemic pattern.

Now in fairness to Marc Lavoie, his piece makes other arguments as well. So what is the nature of these other arguments? The first main one is his own microeconomic argument:

First, consider the microeconomics of the firm. In the post-Keynesian tradition, firms usually operate in an area where marginal costs, or unit direct costs, are constant. Taking into account overhead labour costs and other fixed costs, unit costs are thus decreasing up to full capacity. This means that with a given markup rate over unit direct costs (or with a given markup rate over normal unit costs), profits will be rising for two reasons, as can be seen with the figure below, taken from my 2022 book. First, as firms produce and sell more units, their unit cost drops, and hence their realized profit per unit gets bigger, and secondly since they sell more units, they will make more profits.

This is in essence a more detailed version of my argument in years past that rising sales from government deficit spending can increase profits without changes in prices (or some other expenditure which is not a current cost to businesses.) Direct costs are those costs directly involved in making a product. The insertion of the word “unit” (i.e. “unit direct costs” or “unit costs”) here simply means “average”. The “mark up” on average total costs is simply the profit margin, expressed as a percentage. The “mark up” on average direct costs is a “contribution margin” which is supposed to cover both overhead costs and “profit”. Putting this all together; in the first part he is saying that as sales rise, ceteris paribus, average direct costs remain the same. If overhead costs also remain the same, realized profits will be higher “even though” the mark up he is referring to stays the same. I will return to that point in a moment.

For completeness sake, he also tries to articulate what happens to average total costs. This is despite the fact that his piece is very focused on the “contribution margin”, and average direct costs (a point we will return to.) He says that as sales rise (again ceteris paribus), average total costs fall. Remember that the denominator of the formula to determine average costs is sales, or equivalently, output. This fall in average costs because of rising sales leads profits to rise. However, there’s a problem. He says that the percentage mark up (the profit margin in this case) stays the same. But how could this be so?

If the price is staying the same and average total costs are declining, profit margins must be rising in percentage terms as well as absolute terms. He could rationalize this by saying that “while the ‘realized’ profit margin is higher, companies expect sales growth to reverse and thus they are keeping their ‘budgeted’ profit margins and outputs the same”. Hence his reference to “normal unit costs”. To be clear, what this means is that despite actual sales rising, he is holding normal or budgeted sales constant. I actually brought up this possibility in 2022.

The problem is that this carries us far away from the simple vignette he is trying to paint when applied over time, rather than at one point in time. If sales stay high and businesses keep on realizing higher percentage profit margins, the question arises; why are their budgeted average total costs remaining constant? What is driving their decision not to have “normal”/”budgeted” sales follow the trend of actual sales? Doing this for a year in a highly volatile pandemic environment is one thing. But over multiple years, we need an analytical explanation that Lavoie does not provide. He also does not direct readers to the role of time in his example pricing model. Also note that this rationalization of his piece’s argument involves businesses having sustained discretion over their “budgeted” sales. This is a form of discretion over pricing procedures that his entire piece is devoted to treating as irrelevant. This can’t ultimately bring coherence to Lavoie’s argument.

More straightforwardly, I think that his simplified “Kaleckian pricing model” just does not illustrate what he set out to illustrate. The “mark up” over average direct costs may not be rising — but that’s irrelevant to the topic under discussion. Since the topic is “profits inflation” and not “contribution margin inflation”, what he has actually articulated is a pricing example where a firm (or multitude of firms) are raising target percentage profit margins over time, using their discretionary power to administer prices. The actual accounting data of the U.S. economy he discusses at the beginning of the piece is of average profit margins, and not average “contribution margins”. In similar terms, it’s the Kalecki-Levy Profits equation, not the Kalecki-Levy Contribution equation.

The other problem with Lavoie’s logic here is that his example does not simply assume away “profits inflation” — it also assumes away price increases all together! Prices are constant, while average total costs fall. This leads to the aforementioned rising profit margins (and subsequent rising target profit margin.) Assuming everything else remains constant may be useful for “comparative statics”, or illustrative purposes; But given all the discussion of rising costs during the pandemic, cost increases must be introduced. At that point, the ceteris paribus assumption must be dropped. Once you do that, with the same assumptions about the impact of rising sales on average costs (they go down) and the same assumption of a rising target profit margin he has probably unconsciously made, what happens? You get both “inflation” and ballooning percentage profit margins.

Average total costs could remain constant instead of decline, because other costs rose as sales rose. This thwarts the decline that happens when the only change in costs is the greater “marginal” cost associated with producing more output. This would be a “pure” example of a target profit margin driven price increase. In the other case, average total costs could even rise (meaning total cost increases outpaced sales increases.) That would mean price increases would be both cost and profits based. His pricing example therefore put in a more relevant context, illustrates target profit margin driven price increases. This is quite a significant error. It's a mistake that also illustrates the danger with overreliance on a diagram about what could happen at a point in time when we’re discussing an issue that also involves dynamic changes through time.

To be generous to Lavoie’s approach here, he clearly thinks contribution margins i.e. the relation to direct costs is the important variable economists should focus on. It is genuinely interesting that the “mark up” on direct costs could be constant, even on a percentage basis, but percentage profit margins could still rise. But this is irrelevant to the specific topic at hand unless it could be shown that the overhead cost accounting information was irrelevant to pricing. That would mean that it could be shown that pricing decisions are only made relative to direct costs (meaning business enterprises are only “unconsciously” increasing realizing higher percentage profit margins), that they never become aware of (Or at least, become aware of too far along after the pricing decision to be of relevance.) However, there’s no evidence that this is true. In fact, ironically enough, an internal debate among Post-Keynesian economists three decades ago that Lavoie participated in was focused on precisely this issue.

The late UMKC economist Fred Lee criticized Lavoie and others for using pricing models that didn’t involve the measurement and allocation of overhead costs to specific products, since the evidence shows that businesses, especially large businesses, had already been doing that for decades by that point (at least.) Lavoie and others won the debate on the argument that such differences had no practical importance in economic modeling. The substantive point Lee was making has not only been acknowledged, it makes an appearance in Lavoie’s own textbook:

Whereas, earlier, accountants had only very rough estimates of unit overhead costs, including depreciation costs, this has not been the case for quite a long time. Most firms, large ones in particular, have accurate estimates of unit overhead costs, having found means to attribute to each branch or product the overhead shop and factory costs incurred.

That makes it extremely ironic that Lavoie has written a piece whose analytical premise is centrally grounded in faulty logic regarding average direct costs, average total costs, contribution margins and profit margins. The importance of this issue can’t be underestimated. Simply put: it’s fatal to the argument of professor Lavoie’s piece.

Either he is arbitrarily holding an ever widening gap between “normal” average costs and recently “realized” average costs, or he has constructed the very scenario he was trying to rule out with his toy model. To remind readers: an ever widening gap between constant normal/budgeted average total costs and falling actual average total costs has an equivalent and opposite impact on profit margins. In other words, by accounting definition, if the price is the same and average total costs are falling as a result of sales, this is leading to ever rising actual profit margins. Lavoie utterly convinced himself that average total cost pricing is not significantly different from average direct cost pricing. That means that he could not see that restating his argument in “normal unit cost” terms was no mere formality.

Much of the rest of the piece is devoted to explaining the behavior of something Lavoie calls the “share of profits in value added”. I’ve debated back and forth whether I should tackle this part of the piece at length. Having checked through his textbook and the source his textbook in turn cites, it's unclear why this concept matters. In financial accounting the difference between revenue and costs is the “value added”. At the firm or economy wide level, this is equivalent to total profits. In Lavoie’s long exegesis, he claims that rising “material costs” (raw material inputs and intermediate inputs) will lead to a higher “share of profits in value added” without a percentage change in markups. This may or may not be true…But it does not seem to have any relevance to the conversation about aggregate profits and pricing that the rest of us are having. It's also important to note that this variable is misleadingly named, since the “profits” mentioned are actually the “contribution to profit”, and not “strictly” profits. That’s because its the contribution margin, multiplied by average direct costs — and not the profit margin multiplied by average total costs.

Still, at first glance, this section seems to have some remaining interest to the previous section — since it acknowledges cost increases. However, when you examine things more closely, this conclusion is based on a very strange procedure involving arbitrarily including “average direct labor costs” in the calculation of this bespoke “profits share” measure. This is in addition to its role as part of direct costs multiplied by the contribution margin. I will leave it to interested readers to judge whether the textbook explanation of this variable makes sense. Average material costs may lead to higher prices and higher profits, true. But without knowing the other variables we can’t judge the hypothetical. No one else cares about a value added concept that for some reason includes direct labor costs as well. In fact, as far as I can tell, this “share of profits in value added” can fall as percentage profit margins rise as long as direct labor costs grow relative to the profit mark up. This holds true even if we substitute in Lavoie’s preferred direct cost mark up, leading to the “contribution to profit share” (rather than profit share.) In short, there is far less here than meets the eye. I feel bad even running readers through this conceptual dead end.

To sum up, simply because there are plausible ways to explain rising profits without target profit margins increasing, doesn’t mean that we should. It is an empirical question that needs further study. Lavoie does not provide evidence on actual pricing decisions to judge the role of profits. Likewise, the question of how potentially “generalized” increasing target profit margins might be is not directly relevant to the question at hand. Specific sectors can explain (or not explain) high CPI or PCE growth, and that should be the main criteria. Lavoie also has a strange and unique definition of “profit share” which leads down a road to nowhere. Most critically, Lavoie’s stylized example shows the opposite of what he sets out to show: an overreliance on comparative statics leads to a lack of thinking through what his claims about costing and pricing would mean over time (i.e. a series of pricing periods.) I hope this long read was an educational ride for readers. I will certainly be reflecting more on the Kalecki-Levy Profits equation — and especially its role in the ongoing so-called “greedflation” debate — in the future!

Subscribe to Notes on the Crises

Get the latest pieces delivered right to your inbox