The Night They Reread Pozsar (in his absence)

.

This is a free piece of Notes on the Crises. Pieces will remain free until I feel the fallout from Silicon Valley Bank has fully settled down. To support pieces remaining free, please take out a paid subscription.

Bank deposit insurance is a funny thing. Ordinary people may not know much about finance, but quite a few of them know it's important that their bank is an “FDIC Insured bank”. So deposit insurance is not an obscure feature of today’s society in one sense. What is less understood is that deposit insurance is more than important to ordinary households. It’s important to everyone, and in quite profound ways. Specifically, its limits are important. Most of our modern complex financial system is built up from the foundations of the cap on deposit insurance. It’s such an important and foundational point that sometimes those of us who think about these big picture issues forget to emphasize it. To give an example close to my heart, in retrospect I regret that I only briefly mentioned the importance of the bank deposit insurance cap in my report published last year. This issue deserved a far more profound discussion than I gave it there!

In any case, deposit insurance and the issue of uninsured deposits have jumped into the public consciousness since the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. I gave my first overview of the issue with deposit insurance caps a little over two weeks ago. But today, I want to do something a little bit different. Rather than focus on the trials and tribulations of the uninsured depositor, I want to focus on the consequences of the sophisticated corporate treasurer or asset manager. One who strategizes around the uncertainties of uninsured deposits.

A multitude of voices have claimed that uninsured depositors should not have been saved in this circumstance, because proper “risk management” could have avoided being exposed to such potentially large losses. That may be true, that may not be true. What is certain is that those same “risk management strategies'' have profound consequences for the structure of our financial system that are, to say the least, not unamigiously positive.

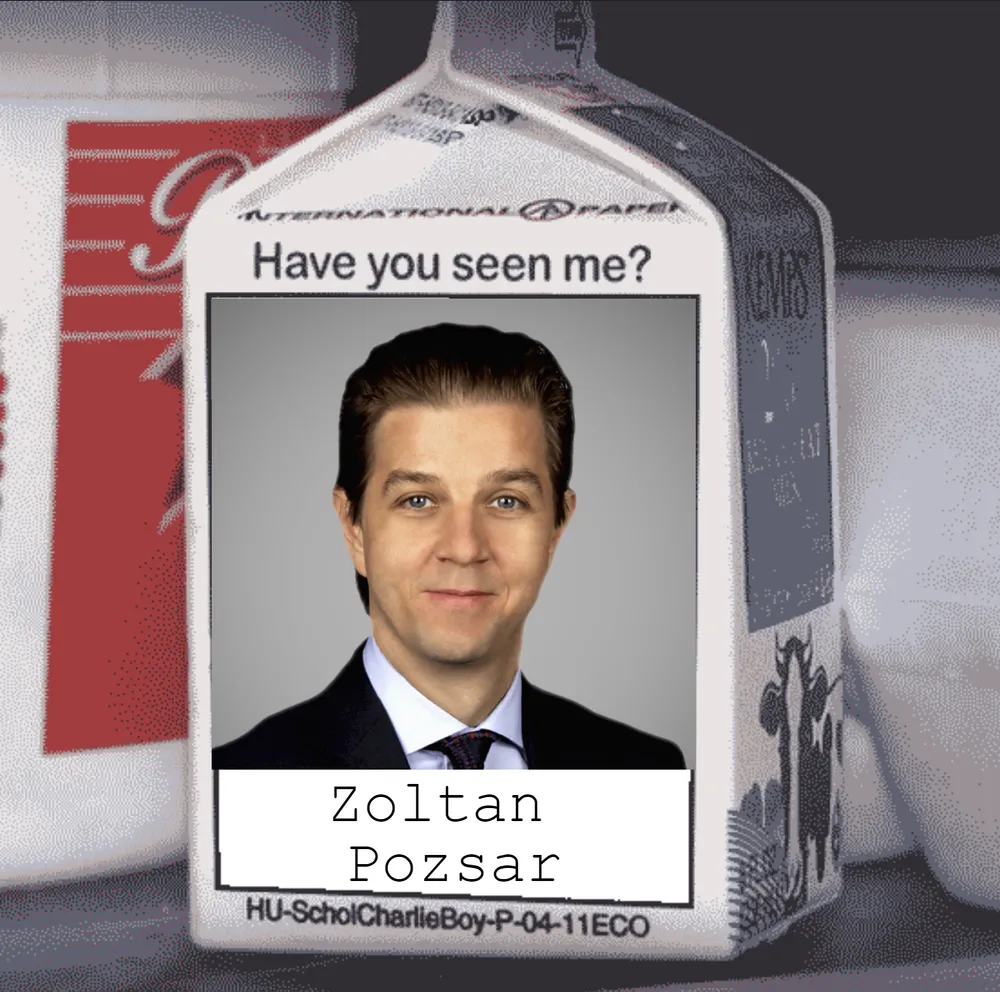

Which brings us to Zoltan Pozsar. No figure is more closely associated with the profound consequences of uninsured deposits for the financial system than Pozsar. He gained notoriety as an expert in the shadow banking system (don’t worry, we’ll return to what this means in a second). Pozsar was himself a key architect of the government’s crisis response in 2008 — from the vantage point of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. While he was a visiting scholar at the International Monetary Fund in 2011 to 2012 he wrote a series of papers on the big picture causes of shadow banking, particularly on the “demand” or “customer” side. From late 2012 to February 2015 he was a senior adviser to the United States Treasury.

On first glance then, you might have expected Zoltan to have been prolific during this crisis. No possible financial market meltdown illustrates the power of his analysis more than this crisis. If 2008 was a Minsky moment, this was a Pozsar moment (of course, Minsky had a lot to say about uninsured deposits too). Yet, Pozsar has been nowhere to be found. Why is that? Well, relevant context is that in 2015 Zoltan left his position at the Treasury to become a Managing Director at Credit Suisse where he has written, among other things, dozens of informative “Global Money Notes”.

As readers may be aware, the failure of Silicon Valley Bank led to liquidity strains at Credit Suisse (which has been a bank with fundamental problems for many years now) that ultimately led Swiss regulators to compel UBS to buy Credit Suisse. It is beyond the scope of my piece today to write a full assessment of these events. What is relevant in this context is that Zoltan couldn’t write about uninsured deposits causing wider financial system strains because those strains targeted his bank, specifically. Anything he would write would have undesirable consequences for his own institution. Stepping back, this is quite funny. The best way I can describe why it's funny is with an analogy: Zoltan Pozsar’s employer being taken down because of a run on uninsured deposits is kind of like Issac Newton dying by falling out of an apple tree.

Since Pozsar is out of commission for the foreseeable future, I think today it's worth rereading his work in the context of Silicon Valley Bank. Let’s take a deeper look at why some of us are not so enthused about these “sophisticated” cash management practices. Supposedly these eliminate the negative (as opposed to the “positive”) consequences of uninsured deposits, but do things really work out that way? Pozsar’s work suggests that the original negative consequences (that uninsured depositors may take a loss), are just replaced by broader negative consequences in the organization of the broader financial system.

The most important paper from Pozsar related to the issue of deposit insurance is a paper entitled “Institutional Cash Pools and the Triffin Dilemma of the U.S. Banking System”. First, some terminology. Pozsar uses the term “institutional cash pools” for those institutions, such as pension funds, university endowments, insurance companies or bank trust departments that invest large monetary sums in order to get a “sufficient” return. Typically, these entities have a fiduciary and/or trustee relationship to others, which provide legal parameters for how these assets should be managed. Economist Hyman Minsky used the phrase “money manager capitalism” for the same phenomenon. Some assessing this development have replaced references to “money” with “asset” i.e. “asset manager capitalism”. This is meant to reflect that only a small percentage of the assets institutional investors invest in are “money” or have a high degree of “moneyness”. For similar reasons, in my work I’ve used the phrase “financial net worth pools”, rather than “cash pools” as Pozsar does.

Whatever terminology you use, the point is that there are a wide set of institutions which manage literally trillions of dollars of assets. Just like you or I do, these institutions have to hold a certain amount of their funds in “cash”, in order to manage their investments and meet outflows. Deposit insurance caps are a problem for this wider network of institutions, because these caps are sized relative to most household “cash balance needs”. By contrast, they are almost laughably tiny compared to the monetary needs of these institutions. This “mismatch” is a gigantic problem. What the financial services part of the financial system ecosystem did ( and does) is create new financial products in an attempt to solve these problems- for a fee. In short, they invented new types of “money”.

Zoltan’s paper zooms in on this phenomenon. Before Zoltan’s work there were large discussions of the “shadow banking system”, but they tended to focus on the incentives that financial institutions had to create “shadow money” in order to hold (seemingly) high yielding assets. Pozsar’s work flips this perspective. Instead he asks, why is there such a large and deep customer base for shadow money? The answer he provides is- deposit insurance caps. It’s worth quoting Pozsar at length here:

As the limits of slicing and spreading growing institutional cash pools in fixed, insured increments across a shrinking number of banks and against binding unsecured exposure limits were reached, institutional cash pools faced two alternatives:

(i) holding uninsured deposits and becoming uninsured, unsecured creditors to banks, or

(ii) investing in insured deposit alternatives—that is, safe, short-term and liquid instruments—such as short-term

(ii/a) government guaranteed instruments or

(ii/b) a range of privately guaranteed instruments (secured instruments and money funds) issued by the so-called “shadow” banking system.

With only a limited appetite for direct, unsecured exposures to banks through uninsured deposits, however, institutional cash pools opted for the second set of alternatives. Relative to the aggregate volume of institutional cash pools, however, there was an insufficient supply of short-term government-guaranteed instruments to serve as insured deposit alternatives [...[ With a shortage of short-term government-guaranteed instruments, institutional cash pools next gravitated—almost by default—toward the other alternative of privately guaranteed instruments

I will return to the issue of “insufficient supply of short-term government-guaranteed instruments” in another piece. For today, what matters is that the key element of uninsured deposits is that they are “unsecured” i.e. not collateralized. This has two issues. 1) you’re less protected against loss because you’re exposed to all of a bank’s potential losses, rather than simply the value of one asset (the collateral). 2) Worse, you have the threat of illiquidity. Even if you will ultimately be paid back, the time it takes the FDIC to fully dispose of the bank’s assets can potentially be quite long. In the meantime, you have a “receivership certificate” which, to say the least, is not an attractive asset to hold. The attractive feature of secured claims- that is collateralized IOUs- is that in case of default you can sell the collateral- and typically quite quickly. Even the extreme case of taking the exact same loss with shadow money that you would have with uninsured deposits favors shadow money because you realize the loss quickly and have liquid funds on hand rather than an illiquid claim that will take- at the very least- months to resolve itself. At least, in theory

Which leads to the negative consequences part. This search for collateralized shadow monies to replace uncollateralized uninsured deposits is not some harmless, costless process. Indeed the very term shadow banking was coined by Paul McCulley in 2007 to describe a set of “non-bank” financial institutions which ultimately themselves experienced a run… A “shadow bank run”, if you will. Recall that the thing that makes today’s shadow money valuable is that “even” in the case of default, and you can sell the underlying collateral quickly and easily. In other words, the collateral is safe and liquid. Just as losses (whether unrealized or realized) can cause a run by uninsured depositors, potential losses can cause a run by shadow money holders. Remember 2007 and 2008? Remember a little instrument called a Mortgage-Backed Security? It should not surprise you to learn that these were one of the key forms of safe collateral which “collateralized” shadow money. Oops!

That there was a “shadow” bank run is one of the less discussed elements of the financial crisis in popular culture but to those of us obsessed with the structure of the financial system, it's a key element of the whole episode. It’s also important to understand that while loss fears triggered these runs, the key deadly element was the collapse of liquidity. Ultimately, the highest rated private mortgage backed securities (AAA) were the principal taken-as-safe collateral for these shadow monies. AAA MBS securities ultimately took only a couple percentage points of losses on average. Remember that, as I explained at length in 2020, Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) are a different instrument entirely.

The point is that ultimately, even the extreme and fraudulent activities which emerged during the 2000s housing boom were not enough to create losses in the safest portion (or tranche) of Mortgage Backed Securities. In this sense, the financial engineering actually worked. The problem was all the financial byproducts (the lower- especially the lowest- tranches) and the inappropriate further use of these financial engineering tools. Again, to learn about this in more detail read my 2020 piece on the topic. Where the financial engineering completely failed is in creating an asset that truly had the liquidity of government securities. The losses may have ultimately been small, but there was no way to know that in the moment. That fear made these assets illiquid.

You might even remember the terminology that emerged at the time to describe this: toxic assets. What the public did not understand at the time is that while fear of losses may have made them toxic, the real issue of toxicity was “liquidity”. The shadow banking system had collapsed as a result of runs which meant the multi-trillion dollar system which financed them no longer existed. The only possible solution was the chartered banking system directly financing the holding of AAA mortgage-backed securities (which it was in no position to do) or else the government stepping in. The money creation process which generated liquidity in these securities markets collapsed and only government balance sheets- i.e. government money creation- could fill the void. You know the rest of the story from here.

The larger issue Zoltan Pozsar is highlighting in this paper is that when you look beyond narrow measures of “the money supply”, deposit insurance is providing less and less protection as these financial net worth pools grow and grow. He says this outright in the paper:

Indeed, if institutional cash pools continue to rely on banks as their credit and liquidity put providers of last resort, the secular rise of uninsured institutional cash pools relative to the size of insured deposits is going to make the U.S. financial system increasingly run-prone, not unlike it used to be prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve and the FDIC. Put another way, the secular rise of cash pools reduces the effectiveness of deposit insurance in promoting system-stability, if depository institutions are wired to serve as insurers of last resort for the world’s uninsured dollar liquidity

Pozsar himself proposes various incremental policy reforms which would limit these issues. He does not suggest getting rid of the deposit insurance cap himself. I briefly touched on the broader range of solutions proposed by a range of thinkers in my piece from earlier this month on Silicon Valley Bank. At some point I will write an entire piece on these solutions, including running through Pozsar’s recommendations in this paper.

Regardless of the potential solutions, I think rereading Pozsar illustrates that the “sophisticated cash management” which has been invoked to criticize “unsophisticated” uninsured depositors has a downside. Shadow bank runs are no better than bank runs. Indeed, in some ways they are worse because shadow banks don’t have direct discount window access. When 13(3) is invoked to effectively give them discount window access, they get the benefits of banking powers without the costs (bank regulation). In this sense, I salute “unsophisticated” uninsured depositors. They have been an unheralded defender of financial stability. We don’t need shadow banking to expand further.

Which leads me to one final topic before I leave readers today. If you look carefully at this piece, none of it is about careful monitoring of balance sheets and credit risks because these “financial net worth pools” do not have the benefits of deposit insurance. Instead, this piece has mostly been about collateral. In some fundamental sense, institutional investors want collateral because they don’t want to do careful credit monitoring. The dream of “market discipline” crashes against a wave of financial engineering in the real world. The Great Financial Crisis involved a lot of complicated factors. One factor it was completely missing was the careful monitoring of credit risks and uncertainties and assurance of borrower creditworthiness. As I said in 2020, ideally creditors would like to replace creditworthiness with collateralworthiness.

Leaning completely on collateral is the opposite of careful monitoring of balance sheets. Asset managers seek out being “fully collateralized” precisely to limit the number of actors whose default uncertainties (and overall credit worthiness) they have to assess.

This is clearest in the case of the latest innovation in shadow money- “cash sweep” programs. These programs, which I discussed two weeks ago, use financial technology to take your large uninsured deposit and break it up into literally hundreds of insured deposits at various banks. If every uninsured depositor used cash sweep type programs, then there would be no “market discipline” i.e. uninsured depositors monitoring bank balance sheets. This would be functionally the same as uncapped deposit insurance, except formally uninsured depositors would pay a fee for that service upfront. Under full deposit insurance, banks would instead have lower interest rates on deposits or find some other mechanism to “recoup costs”. As I said in that first piece discussing all these issues, these “brokered deposits” products essentially transform uninsured deposits into shadow monies. These shadow monies simply have the unique feature that they emerge from within the banking subsidiary, and the collateral is insured deposits themselves.

This is a kind of reductio ad absurdum of shadow money which shows that shying away from eliminating deposit insurance won’t provide “liability side discipline”, it will just generate more shadow banking system instability. At best, these “cash sweep” innovations (and other similar devices) will effectively create a consumer unfriendly version of unlimited deposit insurance. The difference will be that the pressure for corresponding asset side regulation will dissipate in a fog of complexity. Rip the bandaid off, eliminate the cap on deposit insurance and let’s have the real policy debate.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025