What We Learned-And What We Didn't- From the September 2020 Powell Press Conference

Overall, a Disappointing Experience

This article was finished earlier today, but unfortunately substack’s posting mechanism went down for a number of hours. Apologies for the delay.

Yesterday September 16th, as a result of the Federal Open Market Committee meeting, there was a press conference where Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell had to answer a variety of questions from the press. You can see the Federal Reserve’s scheduled meetings- and thus press conferences- here. This conference was particularly important because it was the first one since the Fed had announced significant changes to their operating framework. This gave the press a chance to really get clarity on what precisely the new operating framework meant for our current circumstances. These conferences are also important because they are where the Fed unveils its economic projections for employment and inflation.

So, what did we learn?

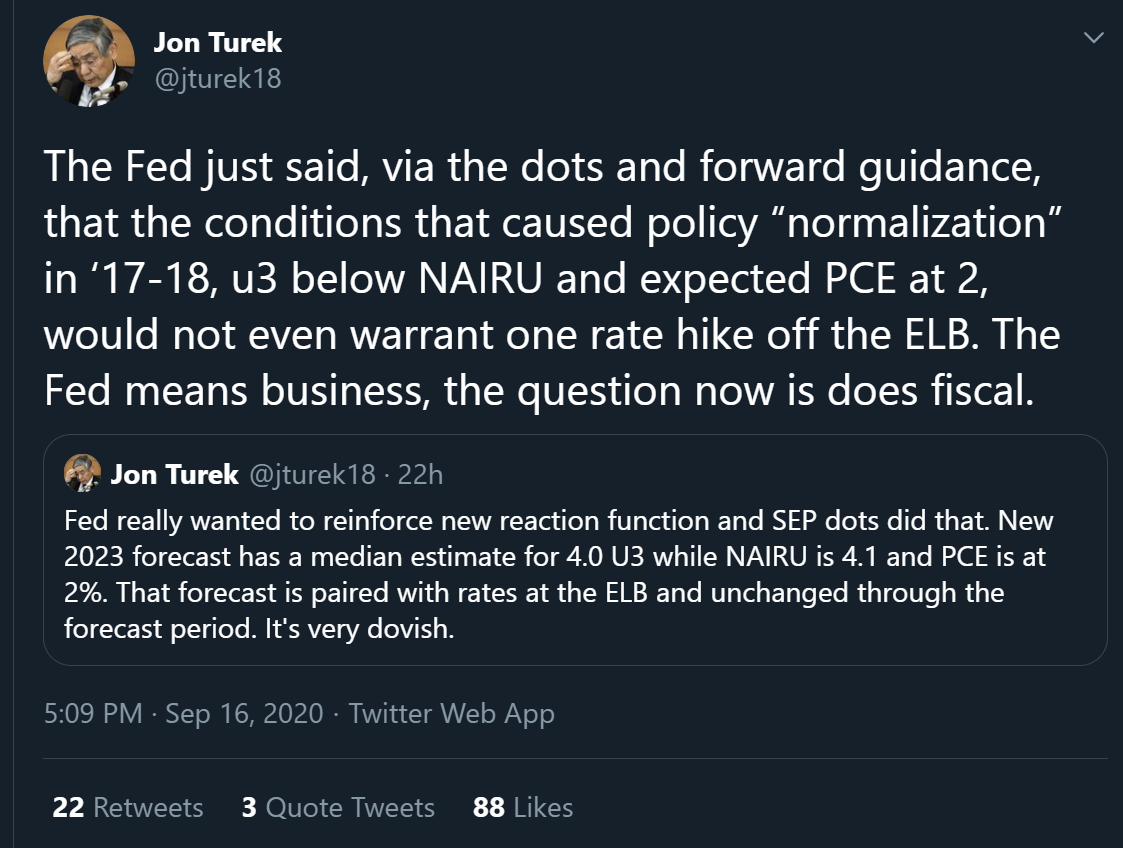

Number one: The Federal Reserve has repudiated it’s earlier policy stances. As Jon Turek (author of the “Cheap Convexity” blog) noted on twitter, the Federal Reserve’s policy guidance says that raising interest rates when unemployment is below its supposed “sustainable” level is a mistake if inflation isn’t coming in “above target”.

The Fed just said, via the dots and forward guidance, that the conditions that caused policy “normalization” in ‘17-18, u3 below NAIRU and expected PCE at 2, would not even warrant one rate hike off the ELB. The Fed means business, the question now is does fiscal. https://t.co/aO9mKxpUwL

— Jon Turek (@jturek18) September 16, 2020

This is important because it is a concrete illustration that the Fed has shifted to a more “dovish” policy and away from its historic tendency to generate unemployment to preempt rising inflation. As I discussed a few weeks ago, this is not a choice to weight their maximum employment mandate “above inflation”. Instead, they argue (based on the experience of the past decade) that the relationship between inflation and low unemployment has changed. Nonetheless, this specific and detailed illustration of what has changed in their policy is good to see and is a genuine improvement

Number Two: It is really difficult to explain the idea of “average inflation targeting”. The notion that periods of higher inflation is beneficial to workers is not at all intuitive to most people, especially as the major inflationary event in recent historical memory, the 1970s, is associated with bad economic conditions in the minds of the public and connected to a burst of cost increases because of energy prices. While I tend not to focus on targets because I think the larger issue is the tools the Fed has- or doesn’t have- to meet those targets, I don’t think inflation targeting is a good communication tool. In this respect, some form of nominal income targeting- whether it’s total income (Nominal GDP), labor income or something else- is easier to communicate.

In recessions it’s easy to say that the Fed is “trying to prevent incomes from falling”. In booms, the idea that if income rises too fast people might buy too much “stuff”, cause shortages and thus “inflation” is far more intuitive. Nominal income targeting is very popular among a lot of mainstream economists, most famously David Beckworth of the Macro Musings podcast. In my view, the rhetorical problem that remains for the Fed is “why should the Fed be doing the nominal income targeting”. While the Fed can obviously influence demand, and thus total income, that relationship is less intuitive to the public and more indirect.

Meanwhile, fiscal policy has a much more obvious and direct effect on nominal incomes. After all, nominal personal income actually rose substantially because of the one time stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits. When the August and September data comes in, personal income will fall further. When the temporary FEMA boost to unemployment benefits runs out, it will turn negative. Nonetheless, the big jump in April and substantial elevation over the summer of nominal personal income illustrates that fiscal policy has a much bigger and much more rapid effect on nominal income. A nominal income target, while being easier to communicate, would make it more difficult to explain why monetary policy is a better tool than fiscal policy to manage economic conditions, especially when it comes time to boost incomes.

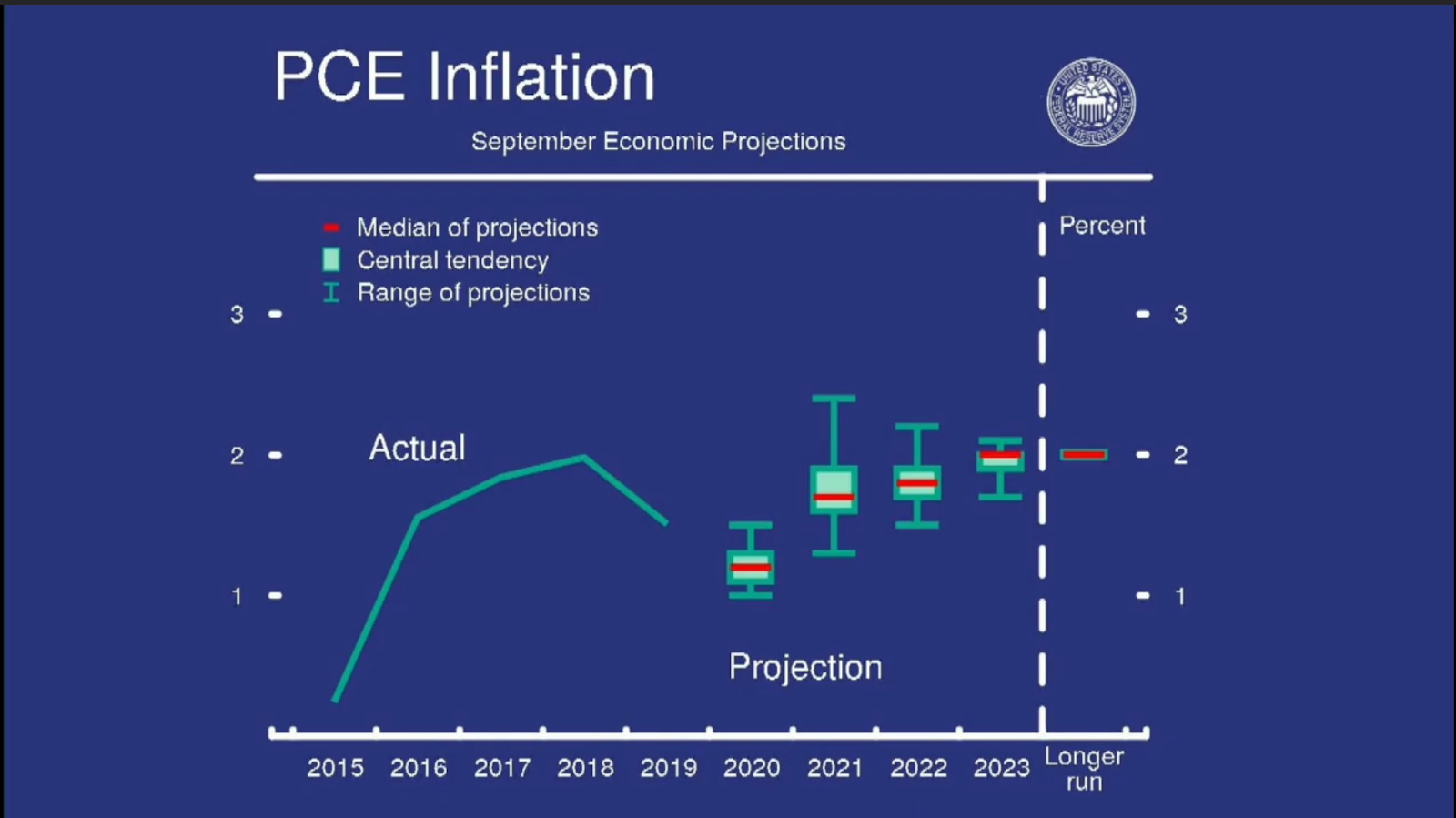

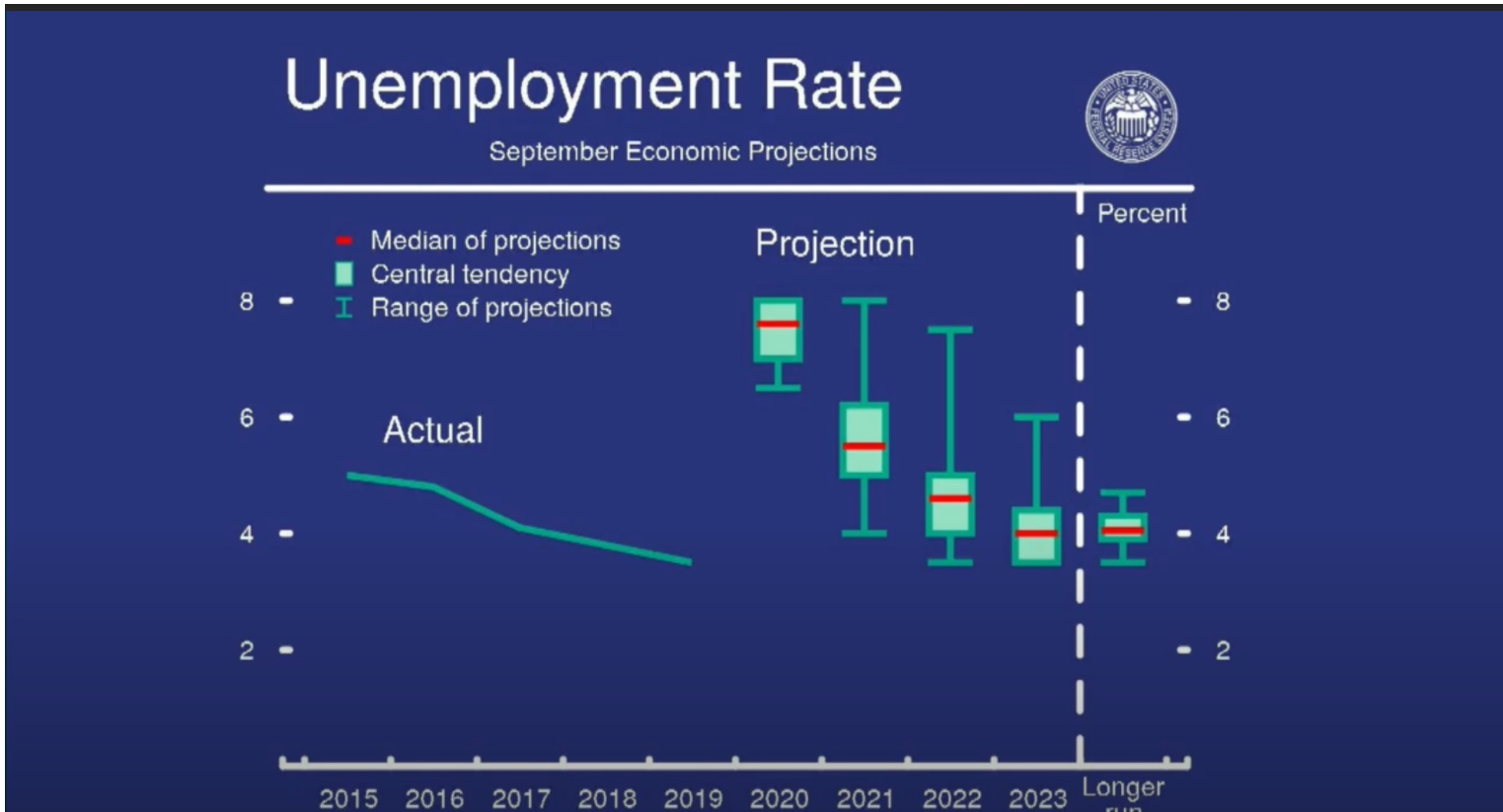

Number Three: The Federal Reserve is still claiming it will hit its targets- “in the longer run”. It’s worth taking a close look at the forecasts of unemployment and inflation that the Federal Reserve is putting out

What is remarkable about these forecasts is that they clearly establish that the Federal Reserve expects to fail for the “foreseeable” future. By their own forecast admission, they are unable (or as I’ll discuss later, perhaps unwilling) to hit their targets. This suggests that they need new tools or another independent administrative agency, likely a fiscal one, needs to be created to hit these macroeconomic targets. Remarkably, the chairman said that this forecast assumed an additional fiscal package from congress, so if congress doesn’t come through (and at this point that seems likely), economic outcomes will be much worse than what they’ve forecasted. Steve Liesman from CNBC had strong questions about their forecast that they wouldn’t be hitting their targets which suggests a multi-year deep recession dragging on. Powell basically dodged the question. Given how little control the Fed has over macroeconomic outcomes, by their own stated viewpoint, the meekness of Powell’s statements on fiscal policy is unacceptable.

Which leads to my annoyance with the “longer run” column in this chart. On what possible basis is the Federal Reserve confident that they’re going to hit their targets in the “longer run”? I mean, look at that inflation forecast! They’re all in total consensus that they’re going to hit 2% on target in the longer run? It is a hilarious form of false certainty that is not convincing to anyone. Some will certainly argue that they can’t, for “confidence” reasons, announce that they will not be able to hit their targets. I have some degree of respect for this argument. In which case, omit the longer run column and don’t insult our intelligence. To me this column reinforces the idea that this crisis is just some turbulence on the road to a return to central bank dominance and unquestioned authority. How many decades do they have to miss their targets before that pretense is dispensed with?

What We Didn’t Learn

I think what we didn’t learn in this press conference is more important than what we did learn. The vast majority of the journalist questions rightly focused on the Federal Reserve’s 13.3 emergency facilities, though there were less municipal questions than I would like. I’m going to make ABSOLUTELY sure that November’s press conference has a question about 14.2(b) credit lines to state and local governments. However, it doesn’t matter that much because Powell’s answers to these questions were extremely murky. For all the bluster about “strong and powerful” forward guidance, it is only interest rates for which we’ve gotten clarity on.

Powell wants to convince people that the Federal Reserve is “not out of ammo” but the Federal Reserve is, by its own forecast, not planning on using these tools to pursue their maximum employment mandate and provide state and local governments with the support they need to avoid reopening prematurely. As I said in my piece on unlimited state and local credit lines:

Federal Reserve officials rightly say that it doesn't make sense to avoid lowering interest rates when the economy needs demand support simply to be able to lower interest rates by larger degrees during recessions. Neel Kashkari recently reaffirmed this point of view on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots. Yet this is exactly how the Federal Reserve has been approaching credit policy when it comes to state and local governments

Powell has not provided clarity on credit policy and their credit policy forward guidance is not consistent with their stated goal to provide “strong” forward guidance which is “clear”. The Federal Reserve needs to pursue its mandate with all of the tools available. Incidentally, this will save many lives.

In some ways, this press conference about the Federal Reserve’s switch to average inflation targeting is from another era. Fed watchers were waiting a long time for the results from their year long review before the Coronavirus Depression. Pre-crisis it would not be outlandish to say that it was the most interesting thing going on in Federal Reserve policy (read- not very interesting). Now we have the results from that long wait- and we’re very underwhelmed. As the journalists did a good job of pointing out, the implementation of average inflation targeting has not actually provided a lot of clarity about their policy. So far, it’s a swing and a miss.

Subscribe to Notes on the Crises

Get the latest pieces delivered right to your inbox