FDR Opposed Deposit Insurance. He Isn’t the Last Word on the Subject

.

This is a free piece of Notes on the Crises.

It’s five weeks to the day since the bank run on Silicon Valley Bank. In that time, intellectual fault lines have solidified. At first dazed, the centrist banking scholars have rallied. In their view many things need fixing. Banking supervision, banking regulation, credit rating agencies, auditors and irresponsible creditors all need fixing. The one thing that does not need fixing: deposit insurance. As the panic has subsided from our mini-panic, the old attacks on deposit insurance have come to the forefront. The age-old claim that deposit insurance “punishes” sound banks (through greater insurance charges) and uniquely encourages irresponsible risk taking have returned with a vengeance. The latest missive comes from the Brookings Institution’s Aaron Klein. Klein's latest, published in the Wall Street Journal, is a piece entitled: “Why FDR Limited FDIC Coverage: The objective was to protect depositors, not rich people and big companies”

The core claim of the piece is that full deposit insurance subverts some sort of original intent of federal deposit insurance circa 1933:

Federal deposit insurance was aimed at protecting the savings of the poor and middle class while leaving the rich to manage the risks of their large deposits. Extending it to large corporations and the wealthy would harm working people.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Banking Act of 1933, it capped coverage at $2,500. The current cap of $250,000 covers about 98% of Americans.

Those who read me regularly will know full well I am on record strongly disagreeing with Aaron Klein’s perspective. It is no secret that I’m an advocate of full deposit insurance and put basically no stock in the “market discipline” supposedly provided by deposit insurance. However, my disagreement with Klein is not what motivated me to write a response to it. Instead, what bothered me was the misrepresentation of this crucial piece of economic and legal history.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was not some principled and long time advocate of partial deposit insurance. Instead, he was a total opponent of deposit insurance who, in the middle of a political fight where new banking legislation was urgently needed, accepted a limited form of deposit insurance. Even more importantly, the proposal on the table was for full deposit insurance and was subsequently negotiated down to partial deposit insurance in congress. Then even still it was FDR’s opposition to partial deposit insurance which held up legislation at a critical time for months.

Now, in fairness to Mr. Klein, I was primed by the headline which begins “Why FDR Limited FDIC Coverage”. Most of the time Op Ed writers do not pick their own headlines so he isn’t responsible for the framing the reader first encounters. Nevertheless, I think his description above also lends itself to the false impression that the system we inherited is a product of considered design… rather than completely opposing visions which were compromised in the end. Before explaining Roosevelt’s place in this story, I think it's worth taking a step back and explaining the congressional context.

The key to understanding how we ended up with capped deposit insurance is to understand a completely forgotten aspect of the Banking Act of 1933. Specifically we have to consider the four provisions known as the “Glass-Steagall Act”. Today the names Carter Glass and Henry Steagall are extremely closely associated. It is barely remembered that there was any difference between them at all. However, the political import of the Glass-Steagall provisions is precisely that they were generated by two important figures who had opposing views on banking reform. Glass, well known for shepherding the 1913 Federal Reserve Act through the house, was a fierce opponent of deposit insurance and focused instead on limiting the investment activities of chartered banks (Glass often referred to those investments as “gambling”).

In contrast, Henry Steagall had been proposing deposit insurance for years. Even more importantly, he was proposing a full deposit guarantee. A CQ Research report from 1932 is worth quoting at length on this point:

Other proposals offered during the present session range all the way from self-insurance of deposits by national banks and bond-surety systems to an outright guarantee by the federal government of the full amount of all deposits in all state and national banks. The bill that will receive most attention is that offered by Chairman Steagall, now pending before the House Banking and Currency Committee.

The Steagall bill would create a “Federal Bank Liquidating Board” to liquidate failed member banks of the Federal reserve system and administer the guaranty fund it proposes. The board would be allowed 30 days for an appraisal of the assets of an insolvent bank. A first payment to depositors would be required 60 days after the failure. This first payment would be not less than 50 per cent of all individual deposits under $1,000, On other deposits 25 per cent would be paid, except where 25 per cent amounted to less than 8500, in which case $500 would be paid.

Six months later the board would be required to pay the remaining 50 per cent due on deposits of less than $1.000 and an additional 25 per cent on other deposits. Depositors not paid in full would receive an additional 25 percent 14 months after the failure. Six months later the board would pay all depositors in full and take whatever assets might remain. These assets would be disposed of for the benefit of the guaranty fund.

Under this system depositors with claims of less than $1,000 would be paid in full at the end of a maximum period of eight months, and all other depositors would be paid in full at the expiration of a maximum period of 20 months.

Thus, the only significant difference between small and large depositors in this scheme is the speed at which they would be made whole. Given that Steagall of Glass-Steagall fame was proposing full deposit insurance, the claim that capped deposit insurance was the wise and well thought out ideal emerging from the “New Deal” looks far more suspect. Which brings us to Roosevelt.

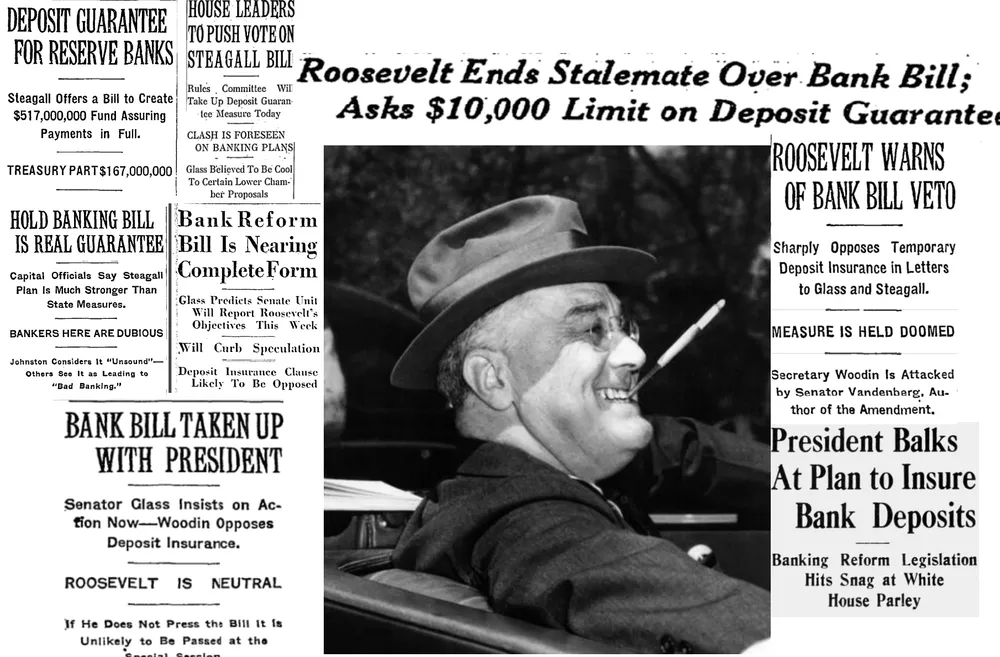

Roosevelt’s role at this time is even more obscure than the divisions between Senator Glass and House Representative Steagall. He was not simply totally opposed to deposit insurance, he held up banking reform for months because of his opposition. As the bevy of headlines in the header image illustrate, banking reform was not simply held up over the issue of deposit insurance: it was specifically held up over Roosevelt’s general opposition. Long after Glass and Steagall had compromised over a partial deposit insurance scheme, Roosevelt was still holding up the process. President Roosevelt’s “off the record” comment to a reporter at a March 8th 1933 press conference probably reflects both his personal and his political opinion at the time:

Any form of general guarantee means a definite loss to the Government. The objective in the plan that we are working on can be best stated this way: There are undoubtedly some banks that are not going to pay one hundred cents on the dollar. We all know it is better to have that loss taken than to jeopardize the credit of the United States Government or to put the United States Government further in debt. Therefore, the one objective is going to be to keep the loss in the individual banks down to a minimum, endeavoring to get 100 percent on them. We do not wish to make the United States Government liable for the mistakes and errors of individual banks, and put a premium on unsound banking in the future.

In this and other comments opposing deposit insurance, Roosevelt reflected the near unanimous views of bankers, especially branch banks (a topic I will return to later). By this I do not mean he was in the pocket of bankers, but simply that his aristocratic opinion reflected their elite opinion. His comments seem genuine to me. The importance of this is that when Klein invokes FDR’s views he is, knowingly or unknowingly, reflecting banker arguments against deposit insurance in general. He is certainly invoking Roosevelt’s arguments against any kind of deposit insurance. If we find those arguments against deposit insurance wanting, then it is more unclear why we should suddenly find them valid in the case of partial deposit insurance.

This brings us to the question of why Roosevelt changed his mind, and why an otherwise lockstep congress so vigorously disagreed with an extremely popular president. The answer, it turns out, is that deposit guarantees were far more popular among ordinary people than FDR in 1933. As historian Christopher Shaw illustrates in his article “‘The Man in the Street Is for It’: The Road to the FDIC”, the public overwhelmingly supported deposit guarantees and they made sure Congress knew it. Nor is there much evidence that these outcries hoped for capped deposit insurance in order to burden the richest or preserve “market discipline”. Democratic senator Robinson from Arkansas, an opponent of deposit guarantees, nonetheless acknowledged that: "the people of this country are very much in sympathy with that idea and they believe that if the Federal Government would guarantee the deposits in all the banks, conditions would be very greatly improved and that prosperity would be promoted." In the same Philadelphia Inquirer article Senator Glass says that 95% of the telegrams congress is receiving are in support of deposit insurance.

Ordinary people, then untrained in the immortal science of means testing, commonsensically concluded that if they thought deposit insurance was important for social stability and economic prosperity, that all deposits should be guaranteed. Furthermore, these people did not take an individual perspective in proposing deposit insurance as a populist economic reform. They saw deposit insurance as not just a means for their own personal consumer protection, but also a protection of their community. Specifically, the protection of small local banks, and the knock on effects of their failures. They saw clearly that deposit insurance limits would mean that the biggest, most well connected banks would benefit at the expense of small banks.

In fact, the concentration of the banking system was Senator Glass’s key alternative to deposit insurance. He saw small banks as the achilles heel of the banking system, and wanted to expand branch banking. For context, the United States had historically had many restrictions on banks having multiple branches, motivated by fear of the concentration of banking. In the 1920s, as both “unit banks” (single location banks) and branch banks grew, there were a number of restrictions on and outright banning of branch banking at the state level. Glass’s theory was that with branch banking there would be a larger diversification of risk, and less exposure to the economic fortunes of depositors in a particular area.

It’s not hard to see how, in the context of depression conditions, the proliferation of branch banking could create a self-fulfilling cycle of perceived protection from risk and deposit flight to large banks. In fact, people understood this at the time. Tennessee representative Will Taylor outright said that “If deposits in all banks were guaranteed . . . money deposited in small cities, towns, and rural sections would be just as safe as money deposited in the large banks of the metropolitan center.” There is nothing new about these debates whatsoever. The two differences between them and us is they were far more familiar with the history of monetary reform debates than we are. And we now have ninety additional years of history and evidence to draw upon that they did not.

It’s also important to remember where we began. Five weeks ago, there was a bank run at a significantly sized banking institution. This bank run is having knock on effects, even though those particular uninsured deposits were covered. Ordinary people ninety years ago had been suffering under years of bank runs and failures. They understand intuitively and viscerally that the burden of bank runs were not simply borne by individual depositors, and their losses — but by entire communities. It was, after all, the Great Depression. That means they understood that leaving a pool of large uninsured depositors would still subject their banks to runs. Indeed runs, even then, were set off by large uninsured depositors and not ordinary retail depositors.

As I wrote about two weeks ago, the growing mismatch between deposit insurance caps and potential large depositors is leading to recurring runs. If they don’t happen in the banking system itself, they happen in the shadow banking system. The consequences of shadow banking runs in the Great Financial Crisis were enormous. The ordinary people who astutely advocated for deposit insurance in the aftermath of the banking panics and failures of the Great Depression understood the great benefits of avoiding such episodes. They advanced this cause despite the protestations of bankers and pundits.

The idea that these benefits are “regressive” would come off to them as very strange to them. So would the idea that we should risk all this social havoc in the hopes that massive bank failures would serve as a random and exploding wealth tax. The record of banking panics is not favorable to such ideas. Indeed, the rescue of Silicon Valley Bank illustrates that the alternative to full deposit insurance is not lack of protection for the richest and most powerful, but protection through governmental lending and ad-hoc actions to benefit them specifically. (That’s also what the Hoover era history of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation shows us.)

If we’re going to treat banks as a public utility, there is a very strong argument for banning buybacks, capping dividends and capping executive pay. You could even tax away the rest of their proceeds as a “franchise tax”. But that’s a story for another time. I also agree that “revenue” from these banks are not sufficient compensation to the public for franchising the ability to create money. After all, I have been advocating qualitative and quantitative credit regulation for a while now. Banking will not be shaped in the public interest without strong public regulation. But deposit insurance limitations provide no public benefits… only the public cost of illusions. Financial institutions innovate alternatives to uninsured deposits as a service, rather than leaving them with the unenviable task of serving as a private banking regulator. They create more financial fragility and instability along the way. The populists were right. We should heed their message, rather than falling into the means testing trap yet again.

Subscribe to Notes on the Crises

Get the latest pieces delivered right to your inbox