Why don't we just provide an Emergency Basic Income to Businesses?

The Small Business Administration's Payroll Protection Program has been a mess

On April 1st I used the Small Business Administration’s Payroll Protection Program as an example of a program from the CARES act congress most egregiously designed from a budgetary point of view:

“The size of the forgivable loans in the Small Business Administration program certainly wasn’t picked based on the enormous need small businesses have to make payroll and rent. What exactly is the purpose of capping the program at a specific dollar amount? When they run out of funds, is the need for small businesses to make payroll any less? Are those who get in their applications after the funds appropriated run out any less deserving of the funding to make payroll payments than the small businesses who got funds?

The reality, of course, is this program is likely to be extended. But when? And by how much money? Will the small businesses who need it now be able to wait for the extended negotiations over extending it?”

As I predicted, the program ran out of funds last week. Congress did indeed drag its feet for a week in negotiations over extending it, finally approving a paltry 310 billion dollars yesterday. In addition to the predictions I made, there were problems I didn’t discuss (though have been concerned about). The structure of the compensation (as well as the incentives banks face in general) meant they prioritized larger and wealthier clients in access to the funds. This was worsened by the structure of the fees, which should have been lump sum amounts (or even provided greater compensation for processing smaller dollar loans) but instead provided compensation based on percentages of loan size. This created the obvious incentive to focus energy on processing large loans for big clients rather than small clients. As if all this wasn’t enough, Small Business Administration rules meant that the 500 employee limit applied per establishment and not per business as a whole so a number of medium sized businesses were able to get access. In addition, franchises of larger businesses also qualify since they aren’t technically considered under the control of their large multinational corporation franchisors. Medium sized enterprises have been returning funds amid the public backlash.

In other words, the Payroll Protection Program has been a mess. Its cap has created a political battle that has reinforced for the public that there isn’t enough to go around so we must fight each other over what little we can eek out. It has created administrative hurdles that have delayed the process of getting money out the door and threatened the capacity for the program to preserve payroll. Its time limited nature has meant that this is only a stop-gap, even for those who get funds. This adds to longstanding problems with the Small Business Administration. It has always had a race problem both in being unwilling to take on additional credit uncertainty (which cuts out Black borrowers with little equity), including not being willing to provide start-up financing. An SBA ruling in 1966 stated:

“While new businesses qualify [for loans to the disadvantaged business community]…we do not intend to provide start-up financing for a small grocery, beauty parlor, carry-out food shop, …[they should not be made] unless there is a clear indication that such a business will fill an economic void in the community.”

Additionally, its slowness in approving loans had greater effects on more precarious Black businesses. However, at least in this period the Small Business Administration was explicitly tasked with (and pursued) providing loans in Black communities. This specific focus on the Black community has been abandoned. In more recent times, the Small Business Administration’s “Minority Lending Program” has adopted a more ‘race neutral’ approach which has left Black small business people behind. They’ve focused on lending to concentrations of already existing small businesses in specific neighborhoods, which disadvantages both existing Black businesses and aspiring entrepreneurs. Their definition of “minority” is also … expansive. As sociologist Tamara K. Nopper says in her excellent article on the subject:

“That is, as long as a certain total of loans are made, the total may be comprised of any combination of minorities, which includes white women [...] by moving toward a more flexible conceptualization of ‘minority’, the SBA publicly promotes the idea that black economic progress has sufficiently been made. [...]. Overt discrimination against black economic development is institutionally treated as a dimension of the past and therefore government ‘intervention’ that occurred during and in response to the civil rights/black power movements is no longer deemed necessary. Ultimately, the SBA’s approach flattens important distinctions among people of color in terms of historical treatment, current experiences with racism, and financial need.”

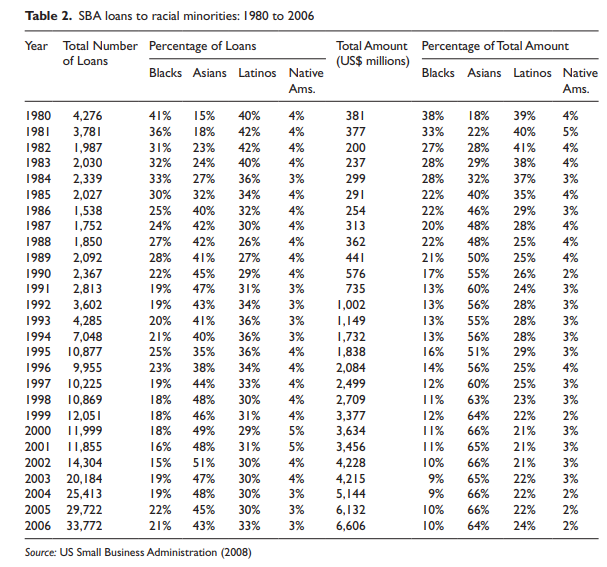

Nopper’s work also highlights why the structure they’ve chosen for the PPP, guaranteeing loans that banks originate, is such a bad one and exacerbates racial inequalities. This structure was adopted in the early 1980s by the Small Business Administration, replacing direct lending programs. There are systematic patterns of discrimination among “mainstream” financial institutions and a lot of reasons to think that those patterns reproduce themselves in reviewing SBA loan applications. As a descriptive fact, Nopper shows that since this switch, lending to Black small businesses has collapsed while falling considerably for Latinx small businesses and growing markedly for Asian small businesses. The numbers have fallen even further since her article in 2011.

The current reporting on access to the PPP shows these patterns have reproduced themselves in this SBA program. As of April 7th, 1/3rd of Community banks (which Black businesses disproportionately rely on) still didn’t have access to the program. Majority Black neighborhoods have disproportionately experienced large bank branch closures over the past decade. Meanwhile, banks focus on servicing existing and larger customers first have boxed out isolated Black small businesses the most. At a fundamental level, the racialized failures of the Small Business Administration in general and the PPP in particular reflect the fact that banks are bad credit intermediaries. They are good at processing payments but not good at evaluating borrowers on behalf of actors whose goals aren’t profit and reinforcing the status quo. Because of their role as credit creators, they are used to being in the driver’s seat.

This brings me to the title of this post- why are we bothering with this complicated structure in the first place? Why rely on banks which are used to providing credit screening when the purpose of our desired oversight isn’t repayment and we want to save as many businesses and jobs as possible? Tax and state regulatory authorities are more equipped at providing the kind of oversight we want- confirming employees of businesses and auditing costs- and are just as capable of initiating payments that the banking system processes. They also already have payroll and banking information of businesses, eliminating problems we’ve had in making direct payments to individuals. We don’t need the stricture of loans at all. We can provide conditionality-lite basic incomes and simply fine businesses who fire employees. We can even impose non-monetary costs such as worker representation on boards of directors.

If we’re worried about payouts, we can do what I’ve already recommended- suspend them. Most importantly this process will be much simpler and involve a minimum of initial regulatory effort. It’s easier to clean up problems after the fact then rush money out the door and do oversight at the same time. We can base this basic income on a formula that includes the number of employees, but also include other demographic factors that struggling Black businesses are likely to have. Even if we didn’t, money directly into your bank account is much more likely to help than a complex bank-administered process that you feel is inevitably stacked against you. Most importantly, by providing it to every business, no one is left behind. Banks are not the right administrative actors for our goal of replacing lost revenue and income and it is far past time we realized that.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025