The Way People Talk About the Federal Reserve’s “Big” Balance Sheet is All Wrong

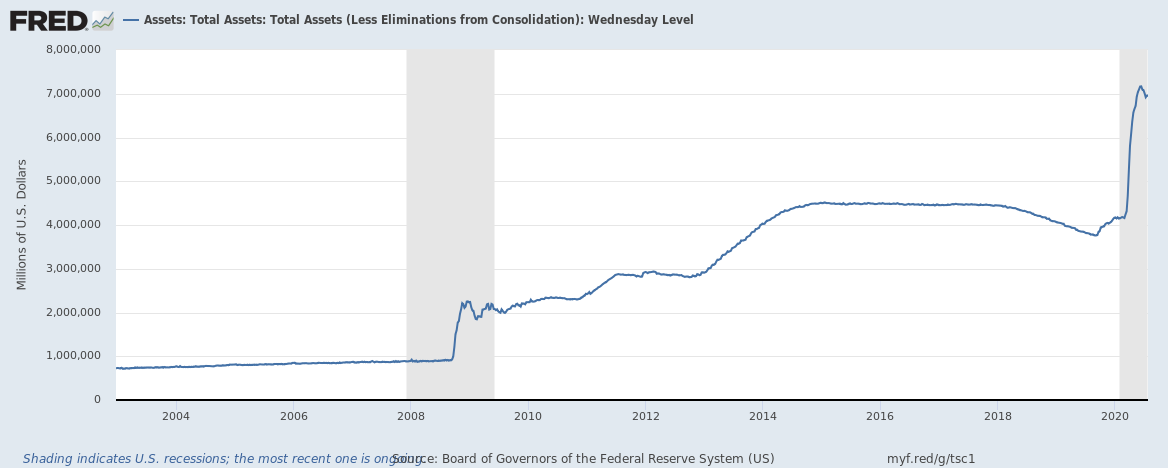

A constant discussion in central banking circles revolves around the Federal Reserve’s “large balance sheet”. I discussed the issues that emerged last September — usually referred to as “repo madness” — all the way back in Part 1 of my series on the Federal Reserve’s Coronavirus actions. These conditions emerged largely because the Federal Reserve had spent years trying to shrink its balance sheet, primarily by not rolling over earlier purchases of U.S. Treasury Securities. For mainstream central banking analysts, a large central bank balance sheet is not desirable, because it is an unwelcome “intervention”, or“distortion” of an otherwise functioning financial market. The large growth of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet in the current crisis has not made these types of commentators happy at all.

I personally find this discussion of the Federal Reserve’s large balance sheet misguided, in a number of respects. On one level, since that balance sheet is mainly made up of government securities, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet could be greatly shrunk quite simply by reassigning responsibilities between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury. All this would require is for the Treasury to directly money finance its spending while authorizing the Federal Reserve to issue its own securities (I wrote about this proposal three months ago). To me this signifies that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet of government securities is not very meaningful. The current set-up is simply a poor substitute for the Federal Reserve being able to issue its own securities (For more on this topic, see here).

On another level, this conversation about the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet ignores how the Federal Reserve implements its monetary policy more broadly. The Federal Reserve licenses financial institutions to participate in U.S. Treasury markets. These financial institutions, called Primary Dealers, are required to make “competitive bids” on every Treasury auction in order to keep their Federal Reserve “license” to be primary dealers. The shrinking of the Federal Reserve balance sheet up until September 2019 simply expanded the primary dealer holding of treasury securities until they couldn’t expand anymore (a point I will return to in a moment). Primary dealers finance their holdings of treasuries by essentially borrowing against treasury securities. This is known as repo borrowing in the “repo market” (check out this #MonetaryPolicy101 post on “Collateral Policy” for more on this). Ever since the financial reforms after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 the interest rate at which you could borrow against treasury securities has been the Federal Reserve’s target interest rate.

In other words, what is the difference between the Federal Reserve requiring a private financial institution to purchase treasury securities, and ensuring they can borrow against those securities at a target interest rate, and simply purchasing a treasury security themselves? It seems to me that the main difference is whether the intervention is overt, or covert. This point goes even deeper though. Part of the reason that the Treasury Market malfunctioned in March is that the primary dealers (and broker-dealers more generally) didn’t have the balance sheet space to absorb all those treasuries. In the old days the lack of risk of treasuries would have meant that both primary dealers and broker-dealers could expand their balance sheets at will. They could do this as much as needed to absorb no or low risk assets. Their only constraint was risk weighted capital requirements. (It’s important to grasp here that most, perhaps all, primary dealers are subsidiaries of bank-holding companies, who are subject to entity-level regulations. This is true of many broker-dealers as well).

After Basel 3 and Dodd-Frank, the largest banks are subject to both liquidity regulations, and a supplementary leverage requirement. This puts an absolute cap on how large a systemically important financial institution’s balance sheet can grow relative to equity regardless of the riskiness of assets (I wrote about this here).

You can blame over-leveraged hedge funds or post-crisis regulations for the malfunctioning in March, and there is truth to these answers. My problem with the way people talk about these markets is the assumption that “full” liquidity is the norm, or a meaningfully “free market outcome”. This is always contrasted with a reduction of liquidity (and associated explicit Federal Reserve action) as “interventionist”. I think this is a false contrast..

Banks are money franchises of the government, given a privileged position in the payments system because of their charters. In this context, even a relatively minor reduction of liquidity provisioning by banks is taken as a major blow to the broader financial system. In my view however, shrinking the scope of activities that banks can undertake is no less interventionist than keeping their franchises loose and broad. As Professor John Haskell and I wrote for Christine Desan’s initiative “Just Money”, regulators allowed the money franchise of chartered banks to expand considerably in the 1990s and the 2000s. This directly led to many of the most grievous problems of the Great Financial Crisis.

So I don’t consider this era less interventionist than the era of the Federal Reserve’s large balance sheet. To me the difference is that the scope of the franchising and sub-franchising of liquidity is more explicit. You can see what I view as contradictions in these worldviews in Economist David Beckworth’s interview with the Bank Policy Institute’s Bill Nelson. Nelson says:

I can see where one would therefore be led to the conclusion that since credit intermediation takes place in corporate bonds, asset backed securities, the Fed has to operate in corporate bonds and asset backed securities in order to bring about the changes in aggregate demand it wants to bring about to achieve its monetary policy objectives. That's just simply not the case. The Fed can have central banks generally operate through influencing risk-free rates, and that should work... There has been over time (and) over the last decade, a significant reduction in the liquidity of those markets as it's become more costly for primary dealers, rather for broker dealers to intermediate in those markets as various regulatory changes have taken place… There seems to be an increasing need for the Federal Reserve to step in potentially be in the market maker of last resort on both sides of those markets. That's not a necessary development.

And as one who prefers that the private sector solve problems whenever the private sector can, I don't think it's a welcomed move. I think it's a dangerous outcome for the Federal Reserve, but there has been an increasing trend over time in which the Federal Reserve is taking actions that increased its involvement in the financial system. I think it's bad for the financial system. I think it's bad for the Federal Reserve.

Nelson’s argument that the Federal Reserve can simply set the “risk-free rate” and arbitrage will do the rest is a common one. This position tacitly requires a world of boundless liquidity. It relies on the idea that there are stable relationships between short term, long term, private and public interest rates. Financial market participants and analysts measure these relationships by calculating the “spread” — the difference between any two pairs of interest rates. The difference between the average rate of interest on short-term private borrowing, and the average rate of interest on short-term government securities is one such spread. This “spread” is interpreted as the additional “price” of borrowing privately to compensate creditors for potential default/volatility etc. The difference between the average interest rate on short maturity government securities and long maturity government securities is interpreted as compensation for “maturity uncertainty”. In principle, any two “pairs” of interest rates can be compared in this fashion. Stable interest rate spreads are a myth and various spreads have risen since the 1980s. But, even to the extent it is true, it requires quite a high degree of franchising and sub-franchising of liquidity by chartered banks to become true. Banks have to lend to non-bank financial institutions and/or themselves participate in a wide variety of markets, to channel liquidity across various different sectors. In my view the increasing liquidity and stability of financial markets, however fleeting they were, could only be achieved by great expansions of financial institution balance sheets which were backstopped by chartered banks and thus, ultimately, the federal government.

In this respect, I think it is a good thing that the distributional choices between corporate securities and municipal securities can now be explicitly observed. We should be debating these distributional choices. I don’t want them to go away after this crisis, through some mixture of rolling back the post-GFC regulations, and stability returning to the financial system. Nor do I think they will. It’s more likely the Federal Reserve will become a permanent player in corporate securities markets. I will push strongly for it to become a permanent player in municipal securities markets (and to provision liquidity on far better terms to these markets). This is especially true if congress lags behind in direct aid to state and local governments. Unlike Nelson and Beckworth, in my view these are choices between forms of structuring and planning financial markets and liquidity distribution The choice is not between “high” and “low” levels of “government intervention”. Rather, the difference between these frameworks is the extent to which the federal government’s actions are explicit or implicit.

Of course, the nature of explicit interventions are changing. Both the Corporate Credit Facilities and the Municipal Liquidity Facility have had very few purchases, but for different reasons. The Corporate Credit Facilities have provided such a strong backstop that private markets have provisioned all the liquidity qualifying corporations need. On the other hand, the Municipal Liquidity Facility is priced so unfavorably that only Illinois has entered the facility’s lone transaction.

This, of course, is another area where the actual size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is misleading. Maybe we should just forget about the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet all together.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025