What the Hell is a Government Shutdown Anyway? The Accounting Gimmicks at the Heart of the Federal Budget

So the federal government is shut down. I’ve been late to covering this story because of my focus on events at the Federal Reserve. Well, that was true when I first wrote that sentence. I then became ill for a full week which has delayed me even more. Fortunately for me, and unfortunate for everyone else, the government shutdown is still underway, so what I have to say is still relevant. There has been so much news packed into this year, it's been impossible to keep up.

To understand a government shutdown, we must go all the way back to the beginning of my coverage of the second Trump administration with my January 31st piece “Everything About the Trump Administration’s Impoundment Putsch You Were Too Afraid to Ask”

As an aside, I got a lot of hate mail- including from long time readers- over my choice to use the word “Putsch” in that headline. While meant to be provocative, it was also meant to be accurate. This has indeed been an “a secretly plotted and suddenly executed attempt to overthrow a government”; since a government is not simply unrestrained executive power. Even our government was not that on January 19th 2025.

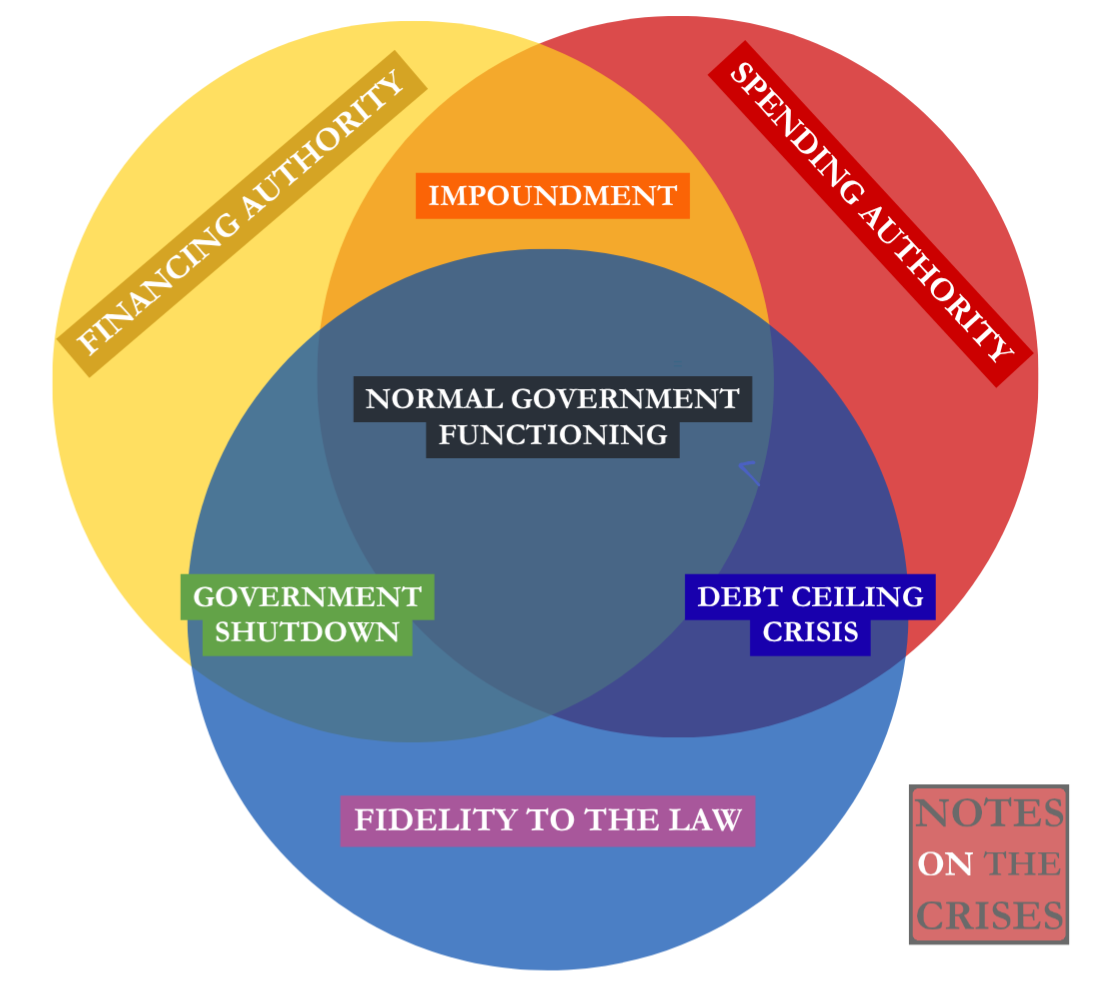

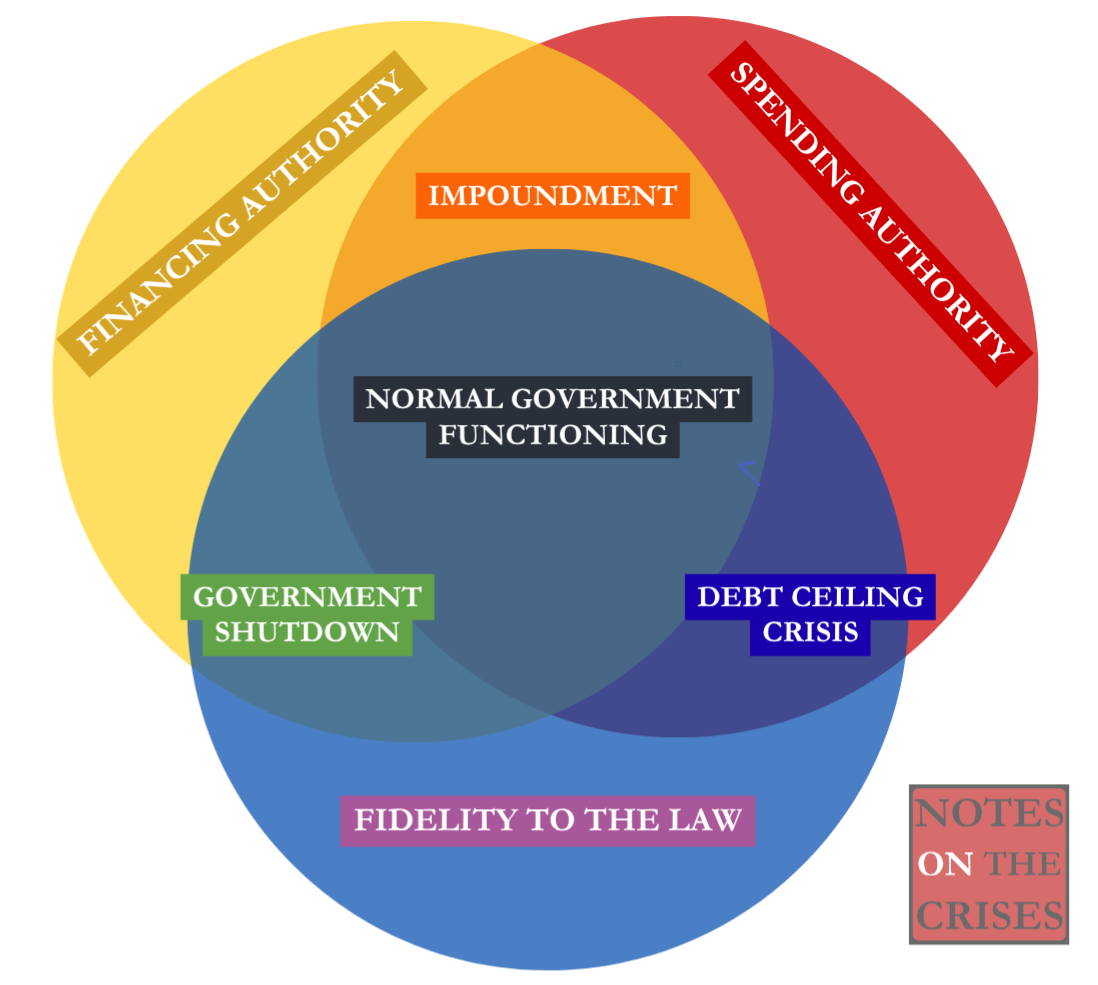

Anyway the reason we need to return to that piece is not rhetoric but the core elements of our budgetary process. As I’ve been hammering for many years, the United States has an extremely unique legal architecture because it separates financing authority from spending authority. You can have spending authority without financing authority— a debt ceiling crisis. Conversely, you can have financing authority without spending authority. In parliamentary systems, this does not happen. Legislation authorizing spending is always simultaneously authorization to finance said spending.

Financing authority without spending authority for many of the basic functions of government is what’s going on now: a government shutdown. This also doesn’t happen in other legal systems because a government unable to pass a budget will fall apart, triggering resignations and/or successful votes of “no confidence”. A ruling coalition must be able to pass a budget to remain a ruling coalition… in a parliamentary system. Not so in the U.S. constitutional system. Our system can remain dysfunctional for long periods of time. We can go years without properly passing an annual budget.

I want to pause here to go deeper on what I mean by “spending authority” and “financing authority”. The press popularly refers to a government shutdown as the government “running out of money”. It’s crucial to understand that this is not true. I don’t think the phrase “running out of money” really makes sense in our system, but let's put that aside for a moment. If “running out of money” could ever make sense in reference to the United States government, it would have to be a shorthand for running out of “financing authority”. I.e. the ability to issue some liability to continue to make payments.

Remember what we’ve learned this year from the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis. Something like 90% of federal government payments run through the Bureau of Fiscal Service’s internal treasury payments system. As long as the Treasury can issue some financial asset- whether its a treasury security or a trillion dollar platinum coin- it can make whatever payments required. The “Big Beautiful Bill” raised the debt ceiling a lot, so it is not currently a binding constraint.

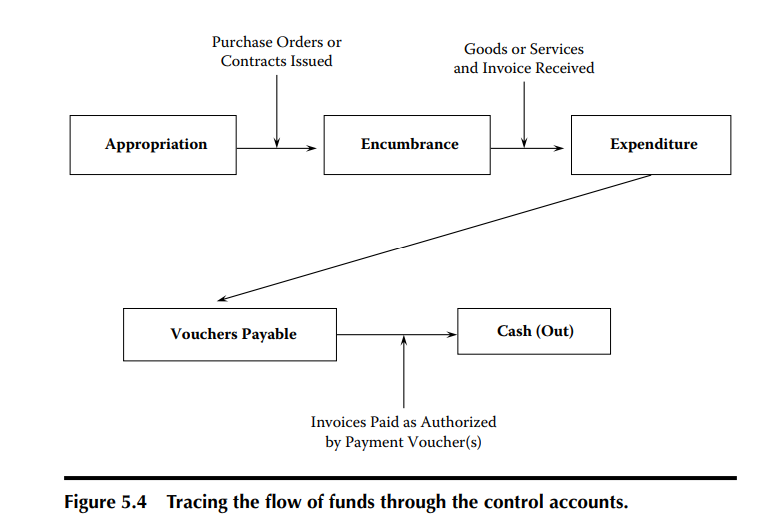

Since the shortage isn’t finance, it's something else- the legal authority to spend. This is known as appropriations. I’m belaboring this point to really emphasize that what is going on now is not about revenue. It's not about “finding money”. What is in short supply is congressional votes. Understanding what appropriations are is easiest to see when each step is traced painstakingly from Appropriation to actual expenditure. See this diagram from Chapter Five of this “Handbook on Governmental Accounting”

I’m so sorry I introduced this diagram. I promise to avoid talking about “Encumbrances”and “Vouchers Payable” as much as humanly possible. Shhh, it's okay the diagram can’t hurt you. The point is that can have all the “cash” in the world sitting somewhere, without any appropriations it can’t be spent. I.e. you need an order to spend to get the “Cash (Out)” process going. Yet government accounting is filled with talk of “funds”. This diagram is from a chapter entitled “The General Fund”. How does that make sense if it's not about “finding” the cash?

Some readers can sense where we’re going next. We’re back to one of Notes on the Crises' most consistent topics: The Law and Political Economy of accounting gimmicks.

The most important accounting construct in governmental budgeting is called the “general fund”. Typically any “revenue” goes into the “general fund”. But what does that mean? You might think of the “general fund” as some pool of money sitting somewhere. But what is truly important about this accounting gimmick is not that money “goes somewhere” but what doesn’t spew out: appropriations. Thus, what's most important about the general fund is not what it does but what it doesn’t do: let a government spend any additional money.

The converse is also true: laws that connect a specific source of revenue with authorizations to spend are accounting gimmicks to provide greater freedom and discretion from the congressional appropriations process. The reason to do so is obvious- this process has gotten more and more dysfunctional. Earlier this year I discussed how Dodd Frank attempted to insulate the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) and the Office of Financial Research (OFR) by directing “bank assessments” to a “Financial Research Fund”. The key is that a “special” or “earmarked” Fund construct authorizes spending that wasn’t being authorized in annual appropriations legislation.

Notice I’m describing both the “general fund” and these “special funds” as accounting gimmicks. One is an accounting gimmick to avoid specific taxes, fines and fees from authorizing more spending while the other is an accounting gimmick to ensure those specific taxes, fines and fees authorize spending. There is no escaping accounting gimmicks so the real questions are whether we’re being honest with ourselves about what’s going on and whether these gimmicks are serving us well.

Which brings us to the current shutdown. Rather than doing a full rendition of the state of play- you can get that from “beat” hill reporting- I want to focus on how the confusion over what I wrote above permeates the popular discussion of the shutdown. A key and fascinating episode has been the White House’s seemingly bizarre claim to use “tariff revenue” to “fund” the “Women, Infants, and Children” (WIC) program. Last week White House press secretary stated on twitter:

The Democrats are so cruel in their continual votes to shut down the government that they forced the WIC program for the most vulnerable women and children to run out this week.

Thankfully, President Trump and the White House have identified a creative solution to transfer resources from Section 232 tariff revenue to this critical program.

The Trump White House will not allow impoverished mothers and their babies to go hungry because of the Democrats' political games.

Since I’m interested in the budgetary law aspect of this, I won’t get sidetracked too much into the question of Tariffs. However, it's important to understand what “Section 232” tariffs are. A colleague in the independent economics writing mines field Joey Politano provided a good summary all the way back in April:

These tariffs will likely be authorized under Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, just like the automobile, steel, and aluminum tariffs already in place. This law allows the President to restrict imports of select goods if they impair US national security, yet the President is only granted these powers after the Department of Commerce conducts an investigation and determines that these imports actually do threaten national security. All the Section 232 tariffs imposed by Trump this year have cited investigations done during his first term, so he would need Commerce to complete new investigations before imposing tariffs on, say, critical minerals. That’s why the administration has already kick-started its investigations into the “threats” posed by imports of lumber, copper, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors.

Those Automobile, steel and aluminum tariffs Joey referenced as “already in place” were introduced in Trump’s first term using executive authority and not rescinded by the Biden administration. That will be important later.

In the popular understanding, this move makes sense. The “government” has “run out of money” and needs to “find it” somewhere. They “found it” in special tariff revenue. As we just painstakingly established though, this is not how it works. Revenue and appropriations are generally separated and are only connected if congressional legislation creates an accounting gimmick to connect them. The Trump administration’s statements have clarified none of this.

Initially, I thought this may be a brazenly illegal move, opening up a new front in our budgetary constitutional crisis. Others thought so too. CNN reported on this possibility:

At least one budget expert questioned the legality of the Trump administration directing tariff funds to WIC. Lawmakers have not appropriated federal funds to be spent on the program, just as they haven’t for the rest of the discretionary federal budget, Chris Towner, policy director at the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, told CNN.

“The problem isn’t that they don’t have the money — it’s that Congress hasn’t told them they can spend it,” he said.

Asked about the administration’s authority, a White House spokesperson directed CNN to Leavitt’s post on X.

A fact that added to this impression is that according to statute, the revenue from section 232 tariffs “goes” to the General Fund. When I looked closer though, I found something different. In particular, I found yet another 1935 law. So much of my writing this year has drawn from 1935. Five days after the Banking Act of 1935 was passed- creating the Federal Reserve as we know it today- Congress passed the “Agricultural Adjustment Act Amendment of 1935”. This August 24th, 1935 legislation has provided the spending authority for a multitude of Agriculture department programs for the past 90 years. The Congressional Research Service concisely summarizes how this works:

Known as Section 32, the fund has three primary purposes identified in law: Clause 1—to encourage the export of agricultural products; Clause 2—to encourage the domestic consumption of farm products by diverting surpluses and increasing their use; and Clause 3—to reestablish farmers’ purchasing power by making payments to farmers. A permanent appropriation of 30% of customs receipts on all imports from the prior calendar year funds the Section 32 account.

So while it's true that section 232 tariff revenue goes to the “general fund” there is legislation on the books which creates spending authority “equal” to 30% of tariff revenue. Let's go to the text of the legislation itself to make sure we are fully clear on the mechanics involved.

There is hereby appropriated for each fiscal year beginning with the fiscal year ending June 30, 1936 an amount equal to 30 percentum of the gross receipts from duties collected under the customs laws during the period January 1 to December 31, both inclusive, preceding the beginning of each such fiscal year. Such sums shall be maintained in a separate fund [...] [emphasis added]

The key here is that “Duties collected under the customs laws” includes all tariffs, even those the president has discretionary authority. There is thus no such thing as a special “section 232 tariff revenue fund. Revenue collected under section 232 simply increases overall “duties collected” and appropriations- spending authority- grows along with the previous calendar year’s total revenue.

Thanks to the Non-profit “Protect Democracy” and its new “Open OMB” project, we have exact information on “Section 32” funds. According to the page devoted to section 32, The mandatory Appropriation in Fiscal Year 2026 (which started October first) was roughly 25.2 billion dollars. Most of this was immediately transferred to other “accounts”, although it's not immediately clear those other accounts could not be “used” to fill in WIC stopgaps. Anyway, according to the information provided here 1.84 billion of budgetary authority was left of “Section 32 funds”. It's not clear what the “creative” part here was, although perhaps what is being referred to us the unused budgetary authority from the previous year which, according to this page, amounted to 387 million dollars. This is a similar sum to the nearly 300 million dollar number that has been thrown around in media reports over this WIC episode.

Anyway, after I did the leg work figuring all this out… I came across a Politico article confirming that this is what’s going on:

The plan deploys authority under Section 32 of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1935, which uses a percentage of customs receipts from imports to support agricultural commodities and other USDA programs, including child nutrition programs. Some leftover dollars from the child nutrition account will be moved to the WIC account.

This episode illustrates a number of things. First, the Trump administration is being surprisingly legalistic and conservative when it comes to spending without appropriations. Second, there is a connection between discretion over tariffs and a discretionary USDA spending authority. This means that Trump’s wave of tariffs this calendar year will greatly increase the section 32 fund in Fiscal year 2027. This is a thing to watch out for. Finally, deep diving this has given me a greater understanding of the “farmer bailouts” in the first Trump term. The very tariffs which set off a trade war with China provides the appropriations authority to give farmers money- helping to solidify their political support. I hadn’t gotten into the budgetary minutia of these discussions when I read about them 5 to 6 years ago. These accounting gimmicks which connect specific revenues with spending authority are the exceptions that prove the rule- while, at the same time, becoming powerful tools for executive discretion and power.

This piece is long, yet I can’t leave this topic without commenting on Impoundment. Our impoundment crisis is not over so, in that sense, we are at two of the Venn Diagram intersection points simultaneously. The last “Continuing Resolution” was March 14th. Six weeks into the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis, my focus was too directed elsewhere to comment. My Second Rolling Stone piece had come out the day before. If I had had the bandwidth to comment, I would have said that passing that “funding” bill made no sense. Budgetary negotiations only make sense if what you fight to be included is spent. In a world of brazen impoundment, cooperating with Republicans to pass a budget is just agreeing with Republican spending priorities while having your own crushed. The conversation over the most recent Continuing Resolution has focused on the Affordable Care Act and healthcare premium subsidies; the crucial issue, however, is impoundment.

Interestingly, in recent weeks Republican legislators have begun openly acknowledging this point. A month ago Bloomberg Government reported that Representative Mike Simpson of Idaho- a senior member of the appropriations committee- credited concerns about cooperating with an appropriations bill given the aggressive impoundment from the Trump administration:

He echoed concerns by Democratic appropriators that it’s useless to strike a compromise funding deal if one side can retroactively block the funds they oppose. “I don’t think the Democrats want to shut down either,” Simpson said in an exclusive roundtable interview with Bloomberg Government. “Their concern right now, and it’s a legitimate concern, is that, how can we agree to any deal when our OMB director will just impound the funds and say we’re not going to spend them there?”

Days before the shutdown began Politico reported this statement:

“If you’re a Democrat — even just like a mainstream Democrat — your predisposition might be to help negotiate with Republicans on a funding mechanism,” said Rep. Steve Womack, a senior GOP appropriator. “Why would you do that if you know that whatever you negotiate is going to be subject to the knife pulled out by Russ Vought?”

As I was finalizing this piece last night Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska made a similar statement, as reported by NBC News:

“If you’re a Democrat, you’re looking at it and you say: why? Why are you going to try to be helpful if Mr. Vought is just going to do a backdoor move and rescind what we’ve been working on?” Murkowski said.

I talked about Vought in my very first piece on “Day zero” of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis but since then I haven’t given him the focus he deserves- in print. I will be correcting that in the coming months.

It is interesting how brazen the Trump administration has been in not honoring congressional orders to spend while being relatively circumspect and legalistic regarding spending without appropriations. Or to put it more plainly, they have yet to systematically spend without spending authority- at least as far as we can tell. There is, however, a gigantic pot of appropriations over the rainbow- and I’m not talking about the tariff accounting gimmick discussed above. But that's… a story for another time.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025