The Longest Government Shutdown in U.S. History Ends Without Ameliorating Our Constitutional Crisis

This is a free Notes on the Crises piece. Consider tipping here.

November is my birth month so I'm doing a birthday sale all month long. I'm turning 34, so an annual subscription is now just 34 dollars. I've never offered subscriptions at this low rate and probably won't again so take advantage now. Thanks for your support!

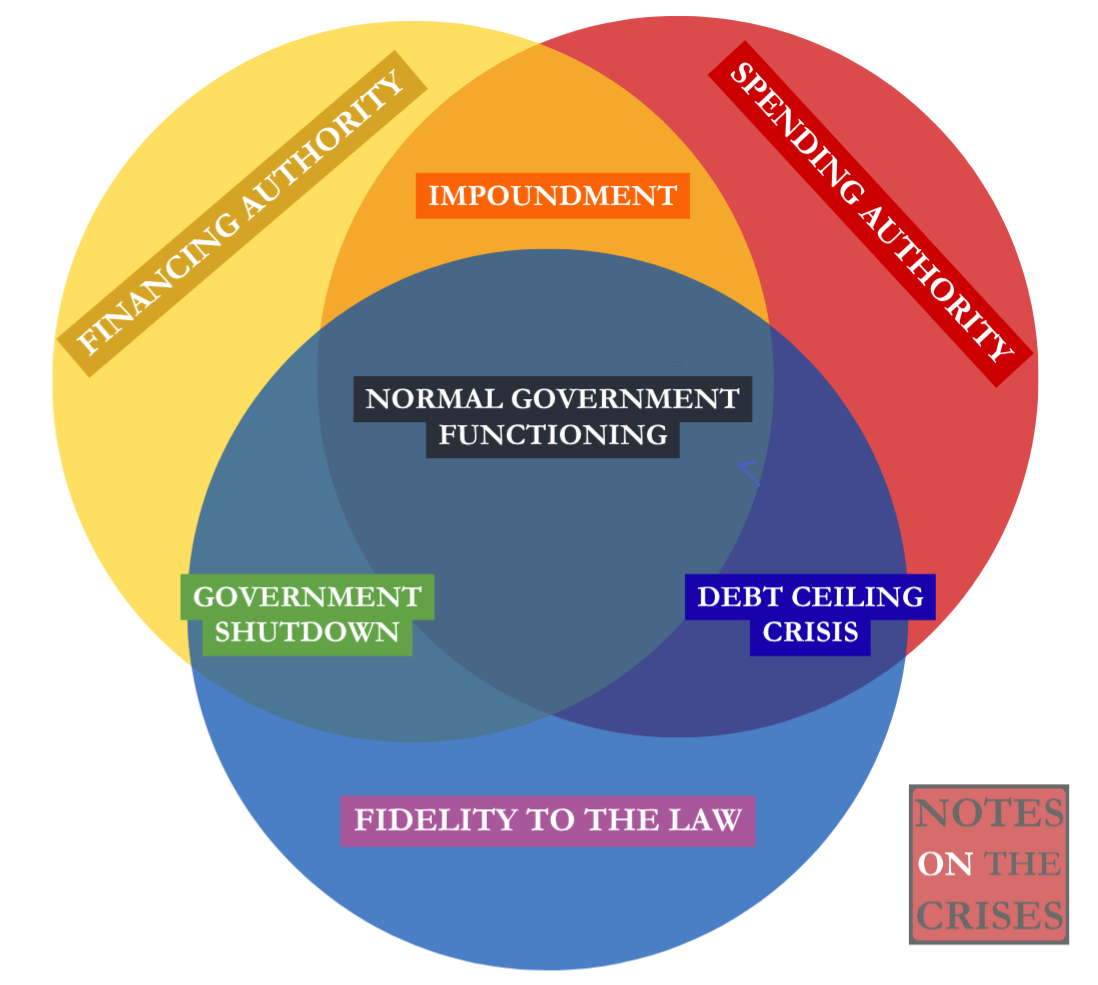

As most readers are probably aware the longest government shutdown in U.S. history, (lasting 43 days) ended Wednesday. I gave my big picture analysis of the government shutdown, and how it fits into our constitutional crisis two weeks into the shutdown last month. Most of my analysis in that piece holds, although there are some unresolved questions: how the Trump administration “found” appropriation authority to continue paying the military, the fast moving and drawn out controversy over SNAP, and the United States central food assistance program. I will take those topics up in a future piece (at least one!) I may yet have to revise my conclusion regarding how “legalistic” the Trump administration is regarding spending “without” appropriations. But today, I want to zoom out and take in the big picture.

In my October piece I commented in passing:

In a world of brazen impoundment, cooperating with Republicans to pass a budget is just agreeing with Republican spending priorities while having your own crushed. The conversation over the most recent Continuing Resolution has focused on the Affordable Care Act and healthcare premium subsidies; the crucial issue, however, is impoundment.

As has now become clear, my statement was too optimistic. The government shutdown has not only failed to address impoundment, it has not even led to any movement to fund healthcare subsidies expiring at the end of this calendar year.

What has been agreed? Not much! Democratic Senate leadership has given up the shutdown in exchange for a “promise” to “hold a vote” on healthcare subsidies in December,. But that is not the same thing as committing to passing anything.

Before getting into the details, I realize I need to step back and explain what a “continuing resolution” is. Congress has struggled to pass a full budget for nearly my entire life. The last time this happened was literally 1997. A “budget” in this case means passing bills authorizing appropriations for various government agencies for a full fiscal year before the start of that fiscal year. Instead, congress has increasingly relied on two stop gap measures:

- One is “omnibus” bills, which package the votes on a series of appropriations into one legislative package (which legislatures must then vote “yes” or “no” on.) Since voting “no” means not funding any of your own priorities embedded in the legislation, that's supposed to create pressure on them to vote “yes”.

- The other is a “continuing resolution” which simply extends the appropriations from the previous legislation into the future (at the same level.) So, for example, if the department of agriculture got x amount of appropriations for an entire year, the continuing resolution would provide for x amount of appropriations (or its “monthly” equivalent.) Continuing resolutions have historically been seen as temporary stopgap measures, or placeholders as yearly budgets got fully negotiated.

Increasingly however, the government has been funded by an unending series of continuing resolutions. When commentators speak about the continuing “dysfunction” of the U.S. legislative budgetary process, this is what they are referring to. And they are completely correct.

Which brings us to the legislation this week. Technically speaking, this legislation is the combination of a continuing resolution with a handful of year long appropriations bills attached. This small package of appropriations bills has been referred to as a “minibus”—since it has some features of Omnibus legislation, but the package of funding priorities only covers a handful of agencies and/or programs. Most notably among them: SNAP. The goal posts have been moved by the crisis—now it's supposed to be a victory that the basic funding for the United States bedrock food security program has been secured.

So what is in our 2025 “minibus”? According to the Republican house appropriations committee press release:

In addition to the continuing resolution, Congress approved three full-year appropriations bills covering the Legislative Branch, Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, Agriculture, Rural Development, and the Food and Drug Administration.

The pattern should be clear: these are supposed to be the most uncontroversial of funding priorities. The flipside then, is that it's even less likely that the “more controversial” funding priorities will be properly funded (since they are not going to be paired with these.) Thus the “minibus” cuts against the incentives that are supposed to be created by “omnibus” legislation. This is a smaller, more subtle, way in which passing this legislation was “caving”.

The continuing resolution itself will only last until January 30th. That means other appropriations legislation will have to be passed by then to continue normal government operations. Otherwise we will… do this all again. That being said, eight democratic senators voted yes—with the seeming support of senate leader Chuck Schumer (who himself voted no)— to end the government shutdown. It thus seems unlikely that there will be an appetite to engage in another government shutdown.

It seems to me that Republican unity, including at the Supreme Court, means that refusing to cooperate with appropriations legislation was the only meaningful form of opposition to the ongoing impoundment crisis. Yet, Democratic party leadership never really framed it as such. Their preferred framing—over healthcare subsidies—has resonated with the public, but didn’t lead to legislative success. Whether a shutdown would never succeed, or democratic legislatures lost their nerve is still open to debate. Regardless, for our purposes, the conclusion that follows is that the impoundment crisis is here to stay.

To cooperate with funding bills in the midst of an impoundment crisis is inherently one-sided. This problem seems to have been mitigated by … Democrats not succeeding to accomplish their funding priorities at all. Yet, even if they had succeeded on the terms of success they laid out, deep problems would have remained. It almost feels as if they lost the legislative battle so that they didn’t lose the war—executive usurpation of the “power of the purse”. Anyway you slice it, this is a story of failure.

Where does this leave us? It seems to imply electoral change as the only thing that will reduce the scale and scope of impoundment. Democrats are clearly hoping that the 2026 midterms yield results like election night two weeks ago. The chaos of the Trump administration and its deep unpopularity clearly speak to these possibilities.

Yet, waiting more than a year for a new congress is a costly endeavor. Every day government capacities are eroded, ongoing government functioning degrades and irrevocable losses continue to accumulate. The government is not a switch that can be turned on and off. It's an extremely complex social and legal machinery that can break in various ways that can’t simply be fixed. To put it bluntly: there could be more mess caused by this annually impounding mess than any subsequent government could hope to tidy up.

At a deeper level, it's unclear how much even the best electoral nights can do to create a legislature capable of constraining executive power. That kind of lasting fix to this worsening turmoil certainly would require far bolder leadership than congressional Democrats—especially Senate leadership—currently show. Our crisis thus rolls on.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025