The Federal Reserve Has Created an Entire Page Dedicated to My Successful FOIA Requests

Tomorrow is my 34th Birthday and as such this month's "Birthday" sale is still ongoing. Take advantage today!

Longtime Notes on the Crises readers will remember that I have been scrutinizing the Federal Reserve using Freedom of information Act (FOIA) requests for a while now. In November 2023 I released the 2011 “debt ceiling default” memo which detailed what the Federal Reserve would do to stabilize the treasury securities market, and consequently the global financial system, in the event that the Treasury was “forced” to default on its payments by a binding debt ceiling. This document is of monumental importance because the full scope of what the Federal Reserve was prepared to do was not clearly and fully understood before that point. Since debt ceiling crises have recurred again and again, the details really matter- which is why the Financial Times covered what I released the same day.

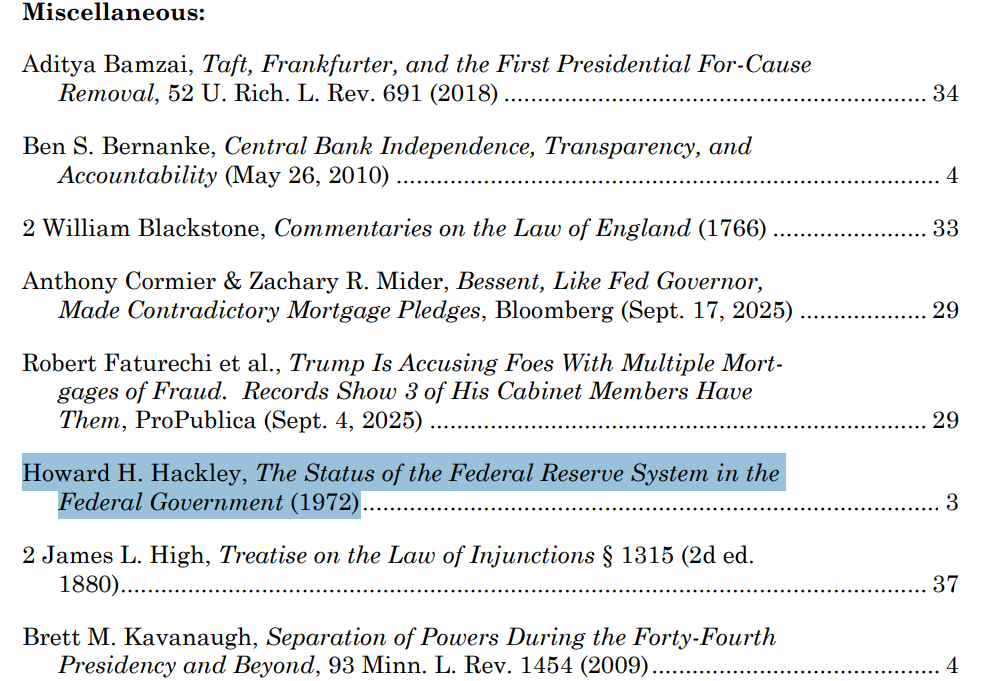

I’ve had a number of other important FOIA successes, one particularly notable one I have discussed many times are the monographs written by former Federal Reserve general counsel Howard Hackley. I was thrilled to notice that Lisa Cook’s lawyers, in the brief they submitted to the Supreme Court, specifically cited and quoted from the monograph “The Status of the Federal Reserve in the Federal Government”. Eighteen months or so between my public release of this monograph and its appearance in front of the Supreme Court of the United States is a course of events FOIA mavens do not dare to fantasize about- I certainly didn’t. That case, by the way, is scheduled for debate in January- with Lisa Cook left at the Federal Reserve for the time being.

As important as all of these are, the crown jewel of my efforts to FOIA the Federal Reserve came in the spring of last year when the Federal Reserve suddenly released to me about 30,000 pages of Federal Reserve Board meeting minutes. I spent months carefully cataloguing this material- with the help of Notes on the Crises intern Josie Grace-Valerius- so that I could publicly release a searchable database of the meeting minutes on this website for free. I finally released that database on November 19th last year.

Almost exactly a year later, I have an important update. FOIA efforts feed on themselves. The more you FOIA, the better you are at FOIAing and the more FOIA successes you have, the more leads you have for… more FOIAing. A crucial thing that government meeting minutes provide is references to documents and correspondence that you can submit FOIA requests for. With 30,000 pages of meeting minutes- covering the critical years 1967 to 1973- I began submitting FOIA requests for individual memos referenced in these minutes. FOIA is all about specificity. The more specific you can be, the quicker you can get a response and the more likely it is that they will grant you the document. With the help of a law school student who interned with Notes on the Crises for the 2024-2025 academic year, I was able to send literally 100s of FOIA requests.

Over the summer I finally began being granted materials I had FOIAed for- after a sea of denials. Astonishingly, at some point in the summer I came across the fact that the Federal Reserve had created an entire page for my FOIA requests. As far as I’m aware, this is extremely unusual for FOIA requests in general and particularly extraordinarily given the paucity of resources I undertook this FOIA efforts with. My FOIA requests seem to be an extremely large part of the Federal Reserve FOIA office’s workflow and creating an entire page for these documents- referred to on the page as “Historical Board Documents”- seems to have been their way of making my project manageable for them. I’m extremely proud of this accomplishment.

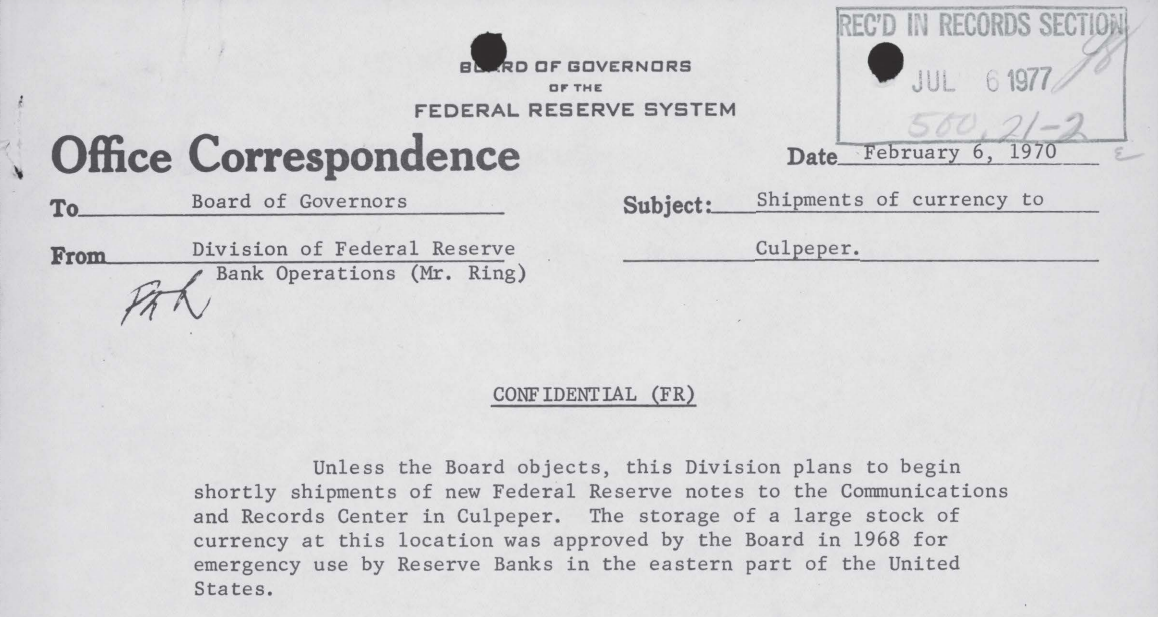

The content itself is quite interesting. I don’t have the time to go through all 52 documents currently on the page as of this writing, but I do want to highlight half a dozen particularly interesting documents. Some of the most interesting documents came in the last couple of months. A short fun document deals with the creation of an emergency currency stockpile in Culpeper Virginia.

The Federal Reserve facility in Culpeper Virginia is of interest because it was established as a key and extremely secure node for “Fedwire”- the Federal Reserve’s network for transferring funds electronically. A 1998 Brookings institution document has a good summary of the security measures at this facility:

Until recently the Federal Reserve Board operated a 140,000 square-foot (13,020 square-meter) radiation hardened facility inside Mount Pony just east of Culpeper, Virginia (near the intersection of State Routes 658 and 3). Dedicated on December 10, 1969, the 400 foot long (122 meter) bunker was built of steel-reinforced concrete one foot (30.5 centimeters) thick. Lead-lined shutters could be dropped to shield the windows of the semi-recessed facility, which is covered by 2-4 feet (0.6-1.2 meters) of dirt and surrounded by barbed-wire fences and a guard post. The seven computers at the facility, operated by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, were the central node for all American electronic funds transfer activities. [emphasis added]

Okay, it was the key point for wiring payments across the country. But why were they shipping physical currency there?

In preparation for Nuclear war of course. I’m not kidding:

Until 1988, Mount Pony stored several billion dollars worth of U.S. currency including a large number of $2 bills shrink-wrapped and stacked on pallets 9 feet (2.7 meters) high. Following a nuclear attack, this money was to be used to replenish currency supplies east of the Mississippi.

Lets just say that this is an unusually dramatic topic for a Federal Reserve memo.

The February 6th, 1970 memo is short and a fun read but its conclusion basically communicates what it focuses on:

While some risk will be involved in storing currency at Culpeper in the absence of detailed arrangements for military support and a better means of communication with the state police, it is felt that the risk is not great enough to warrant a further delay in the development of this emergency stockpile. Efforts to establish a protected direct line of communication to the District Headquarters of the Virginia State Police, and to make detailed arrangements for military assistance will continue. [emphasis added]

Robbing the Culpeper Virginia Federal Reserve facility’s emergency currency stockpile in case of Nuclear war in the limited period where they hadn’t fully established their security measures would make for an excellent movie plot. Die Hard Three eat your heart out.

Most of these documents will not live up to this one but they remain quite interesting. As longtime readers know I’ve been obsessed with the secret history of the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending powers so it's unsurprising so many of these memos are related to that. So many of these are related to the Federal Reserve’s response to the bankruptcy of the railroad Penn Central- a key moment in Federal Reserve history where the system first considered lending to a non-financial institution for the sake of systemic financial stability.

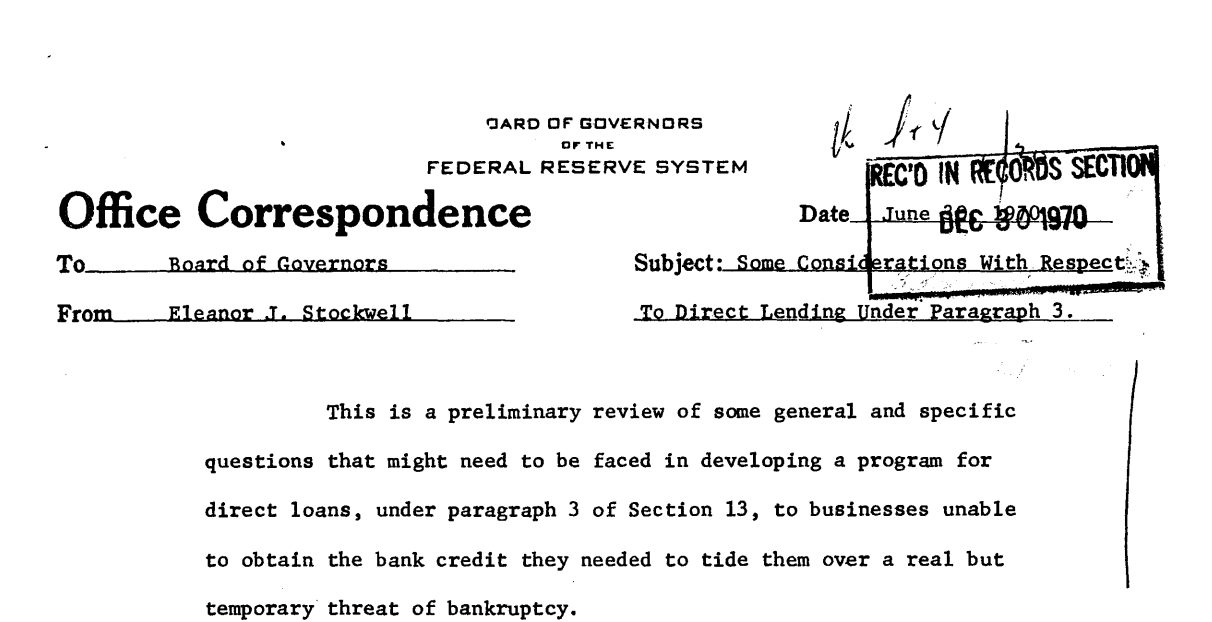

The most important and extraordinary of these is a memo written by long time Federal Reserve employee Eleanor Stockwell. Dryly titled “Some Considerations With Respect to Direct Lending Under Paragraph 3". Conspicuously dated 9 days after Penn Central publicly declared bankruptcy, the document clearly shows that most of the questions that only came to public consciousness in 2008 were first debated and seriously considered in secret among Federal Reserve officials 38 years prior. The memo is short and clearly written and its contents are so striking that my attempts to pull a representative quote has brought me dangerously close to just copy pasting half of the 7 page memo’s contents. I will thus confine myself to this single paragraph:

Third, what constitutes "unusual and exigent circumstances"? Must there be some potential injury to the general economy or at least to other businesses, if a particular firm should fail? In a sense, this is the converse of asking whether, despite its strong economic and administrative justification, it is politically feasible for size of business to be a criterion[?] [emphasis added]

It's hard to imagine how history may have been different if this debate had been a public one rather than one held in secret nearly four decades before the public became aware of the consequences of their thinking.

There are also interesting documents on the Federal Reserve’s “funding” of its “retirement system”, the Federal Reserve Board’s assessment of Federal Reserve Banks to fund its operations, spending on architectural services and the regulation of the issuance of commercial paper by large bank-holding companies, among many others. I’m sure I will draw on these documents in various commentaries for years to come.

I unfortunately have not had the time for this FOIA project that I had last year as a result of the extreme and extraordinary events of this year. But I have not forgotten about it and I’m committed to sustaining it over the long haul- and I’m extremely grateful for the help student interns- and other anonymous people- have provided to these efforts. While these materials may not be headline grabbing, it is this kind of slow and painstaking work which has helped to build up my understanding and expertise in far ranging issues regarding the payment system, the financial system, financial regulation, sanctions, fiscal policy and more. I was able to provide a comprehensive guide to the “intragovernmental” payments system and how it interacts with so many other moving parts of the Federal Government over the course of a weekend at the beginning of February because of such slow and exhaustive efforts over many months and years.

The usefulness of this work is obvious in a crisis, but by the time the crisis arrives it's too late to go about gathering that knowledge. Thus, if you appreciate this investigative work- along with all sorts of other research and analysis Notes on the Crises does- please consider taking out a subscription in this “quieter” period. I am long overdue for providing major updates about the “Trump-Musk” payments crisis but in the meantime I can say that I’ve been organizing a new effort to take the FOIA skills I built up on the Federal Reserve and apply them to impoundment and budgetary issues more generally. I can’t say more at this stage- but more soon.

Finally, I would like to remind readers that it is possible for institutions to take out subscriptions to Notes on the Crises. Academic libraries and other non-profit institutions can subscribe for $2500 dollars a year while for profit enterprises can subscribe for $4000 dollars. A new capability this service has is automatically granting “comped” subscriptions to individuals who sign up to Notes on the Crises from their institution’s email address. For example, if the New York Times had a Notes on the Crises subscription, anyone who signed up from “@nytimes.com” would automatically get a free premium subscription. You can find more details about institutional subscriptions in my announcement last year.

Most importantly however, having an institution that a reader is affiliated with- or a client of- subscribe helps provide long term support to investigative efforts that individuals can’t or won’t personally compensate for. Investigative work takes so many hours- frankly more hours than it would ever be possible to compensate for. Since I think FOIA research is a public service, I want to always avoid paywalling documents. Institutional subscriptions help expand investigative efforts without fear of failure or setbacks. Contact me at my email address to inquire regarding more details about institutional subscriptions. I also have a couple important institutional subscriptions I would like to announce publicly but need more institutions to announce at the same time.

That’s all for now, and thanks as always for both your attention and your support.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025