Can China “Buy” America? Fifty Years Ago Last Week the Ford Administration Created the Government Body That Stops That From Happening.

I have ended up taking a lot longer to write up my biggest picture thoughts on the dollar than I initially expected. Partially this is because things seem to have stabilized- for now- and thus I didn’t feel the pressure to rush a piece out. Just yesterday China and the United States announced a tariff agreement- at least for the next ninety days. But the other reason I haven’t put out a big picture piece on the dollar is I have struggled to put all my thoughts on this topic into one piece. Before the coronavirus pandemic- when I was in a very different place in my life- my goal was to go off to undertake a PhD in law in Europe where I would write a three chapter dissertation on the international law of money. My June 2018 talk which I published in the newsletter last month provides the rough skeleton of my thinking. How do you get all of that into one piece?

Which brings me to what I’m writing about today. The week the Trump Tariff Financial Crisis broke out I began watching Fox News during prime time each day. I’ve long tried to periodically catch up with Fox News because the stories on Fox News do not appear anywhere else and are key to understanding the right wing political spectrum in the United States. I have a very vivid memory of first encountering Vivek Ramaswamy- who was very briefly co-head of DOGE- by watching Fox News in late April 2023. Most importantly Fox News is the main media source President Donald Trump watches so if you want to have some insight into his thinking, Fox News is a crucial source. This is especially true because Trump officials, including Trump himself, influence what Fox covers by directly talking and cajoling it.

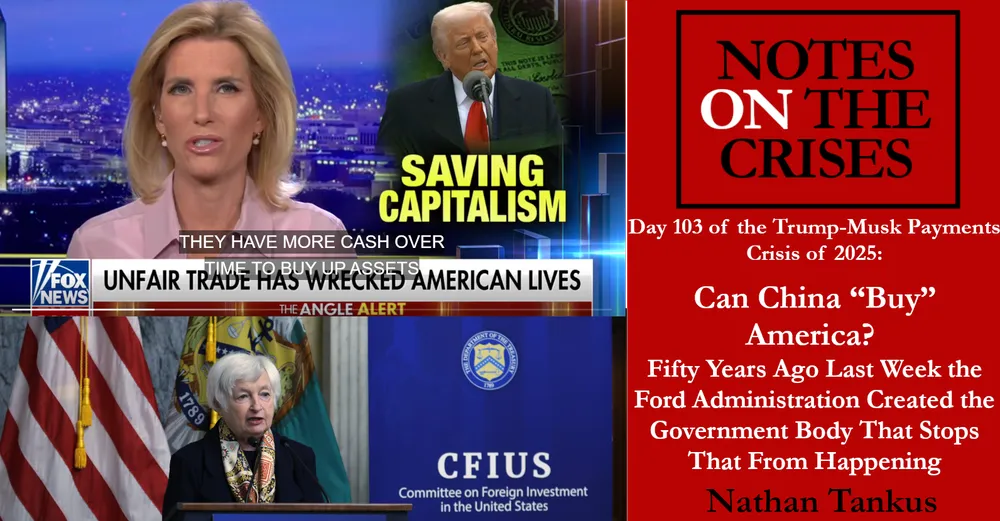

Turning back to the Trump Tariff Financial Crisis, the most interesting segment on Fox News I watched that week was a Tuesday, April 8th segment entitled “Saving Capitalism” at the start of “The Ingraham Angle” with Laura Ingraham. Watching this segment was what fully convinced me that the tariffs on China would go into effect at midnight. I began writing Wednesday morning’s piece with that conviction in mind before going out to a friend’s birthday party. I started heading back home around midnight and caught up with the fact that the financial stresses I had started to write about had already begun leading to various different financial dislocations.

But that I’ve already covered. What I noted in my head at the time, and I’m writing up in today’s piece, was the longer historical narrative Ingraham painted. She hammered on Trump’s rhetoric that these sudden global tariff moves were the “last chance” to save the American “middle class”. One key focal point of her narrative was that by running trade surpluses with the United States China could accumulate dollars and “buy America”. I found this so interesting because these fears have recurred over the last 50 years, but the Fox News narrative neatly cuts out that this is a solved problem. In fact, it was solved by an institution created exactly 50 years ago last Wednesday.

When OPEC quadrupled its posted oil price more than fifty years ago, and subsequently major oil exporters began to run large trade surpluses, Americans quickly fretted about the power of these countries. The symbol of the danger in this new world order was a stereotyped caricature invariably labeled Saudi Arabia. One major component of this worry was the ability of OPEC countries to “buy up America”. I think it’s interesting how much fear the United States has had of foreign control given the dominance the United States has had over other countries. But that’s a question for the psychologists, not technical economic policy analysis.

One of the best books on this topic I’m familiar with is a 2018 book by Georgetown professor Ashley Lenihan named “Balancing Power without Weapons: State Intervention into Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions”. As the book recounts, president Gerald Ford created by Executive Order 11858 of May 7, 1975 the interagency Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States” (CFIUS) and empowered it to regulate foreign direct investment. As Linehan recounts, the Ford administration CFIUS was created “in response to mounting concern over a rise in foreign investment from states within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which was feared to be politically motivated in the aftermath of OPEC’s 1973–74 oil embargo”.

This interagency body, chaired by the Treasury secretary, can simply stop overseas mergers and acquisitions of companies, purchases of real estate and even significant minority purchases of the stocks of a single company. Just like with Index Funds, foreign governmental entities are required to be “passive” investors and not attempt to actively control a company. When Sovereign Wealth Funds first came to prominence two decades ago, the United States quickly launched into action to establish a “global framework” for how Sovereign Wealth Funds behaved and to ensure their “passivity”.

CFIUS initially prevented foreign direct investment into companies with sensitive national security technologies and, over time, increasingly disfavored investments in all sorts of companies because of vaguer and broader “economic security” concerns. While CFIUS was created by executive order, the presidency gained additional powers which it could delegate to CFIUS in the following decades. The 1980s fears of Japan “owning America” led to new statutes which granted new powers and even required certain kinds of national security reviews of mergers and acquisitions. Above all CFIUS dissuades foreign entities, especially foreign governments, from buying controlling shares of U.S. companies. In fact, there is already a long history of using CFIUS to prevent the acquisition of various “strategic assets” and companies by China. Professor Lenihan’s book is filled with an enormous amount of discussion- and policy history- on CFIUS and China.

This no doubt is an important structural contributor to the subpar performance of foreign equity investment into U.S. companies relative to U.S. subsidiaries and equity investments abroad. Thus, not only do we already prevent other countries from using dollars to take control of key strategic resources, we parlay that into an overall financial advantage. Put simply, the United States profits from control of foreign resources without allowing foreign control of domestic resources. The only “cost” was allowing open access to selling goods and services in the United States. The very limitations these foreign countries are subject to opens up the question “is it even really costly for the U.S. to run trade deficits?” Unfortunately, that question brings us back to the overall question of the dollar which is beyond today’s scope.

Some might object to my characterization here based on the fact that CFIUS only looks over and examines a small amount of the total mergers and acquisitions and generally does not have a large scale. What this argument misses is the very existence of CFIUS, and the statutes that lie behind this, dissuades foreign countries and companies from engaging in economic activity they otherwise would in the absence of this regulatory regime. You only have to look at the purchases and acquisitions the United States, and U.S. companies, make abroad to see the difference.

What does all this mean for the second Trump administration? The way I look at it, the attempts to make Trump’s approach to world economic policy make sense requires ignoring the long and storied history of the Federal Government. Trump wanted to press a button to make trade deficits go away- causing global financial stress in the process and emptying our shelves in the process. Little does he know that the U.S. federal government long ago built buttons to make the accumulation of dollars by foreign countries benign. But imagine trying to explain CFIUS to a Fox news audience.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025