Can Taxing Capital Flows Close The United States’s Trade Deficit?

Premium Post #3

On twitter this past week someone asked me about Michael Pettis’s proposal to tax “capital flows” as a way to close the U.S. Trade deficit. I replied at the time, but I’m going to write a more formal criticism of this proposal for this weekend’s premium post as I think it's an interesting issue but more niche currently than a lot of the other things I’ve been writing lately.

First though, what actually is Pettis’s proposal and what problem is it trying to solve? The best place to get the answer is his article straightforwardly titled “Washington Should Tax Capital Inflows” which he wrote for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The core of the proposal is nicely summed up in this quote:

The purpose of the tax would be to reduce capital inflows until they are largely in balance with outflows. A country’s capital account and current account must always match up exactly, so a balanced U.S. capital account would mean a balanced current account, and with this the U.S. trade deficit would disappear.

The logic behind this is motivated by basic national accounting. In national accounting the “current account deficit” is made up of three types of income

- Net Goods and services sales (trade deficit or surplus)

- Net income (dividends, interest, resident salary etc.)

- Net transfers (international aid, remittances)

Excluding paying down debts, acquiring a surplus in one or all three of these ways requires acquiring assets from foreigners. This is often described as “exporting capital” and as money “flowing out” of a country but it makes more sense to think of this in terms of asset acquisition and disaccumulation. To understand this point let’s return to the building block of monetary transactions- the payment between individuals.

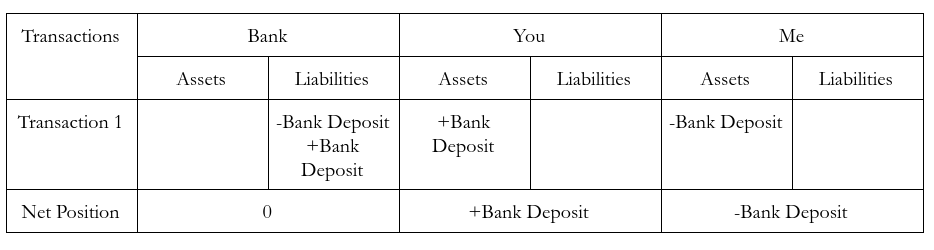

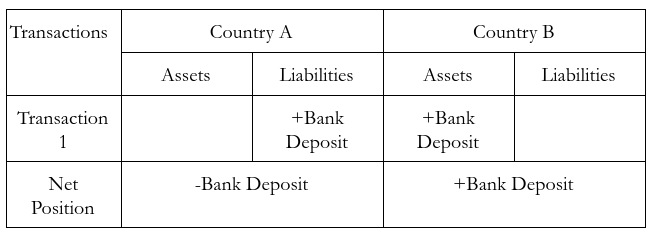

In our personal lives, it’s obvious that money in this circumstance is flowing away from me and towards you. Yet, in the balance of payments, this is seen differently. Imagine that the bank in this circumstance and myself were one country and you were your own country. To simplify things, I’m going to exclude intra-country transactions. When you do that, this set of transactions simplifies to the emission of a bank deposit from Country A to Country B.

So why do some people think of this as Country A “importing capital” and Country B “exporting capital”? Because choosing to continue holding the bank deposit (or purchasing stocks or bonds in Country A) rather than using it to pay a resident of Country A for goods and services is choosing to remain a creditor of Country A. Meanwhile, at the aggregate level, Country A is becoming indebted to Country B which is sometimes also thought of as Country A “net investing” in country B. As we can see though, that kind of thinking can lead to confusion. All that’s happened is a resident of Country A made a payment to Country B. No one is choosing to invest (at least not initially), nor is choosing to receive “net investment” from abroad in this scenario. It is far more useful to think of these net positions between countries as resulting from a series of payments than as a result of investment decisions, financial or otherwise. To see why, let’s examine what happens when a Chinese resident buys a USD Bank Deposit from a U.S. bank in order to make an investment in the United States.

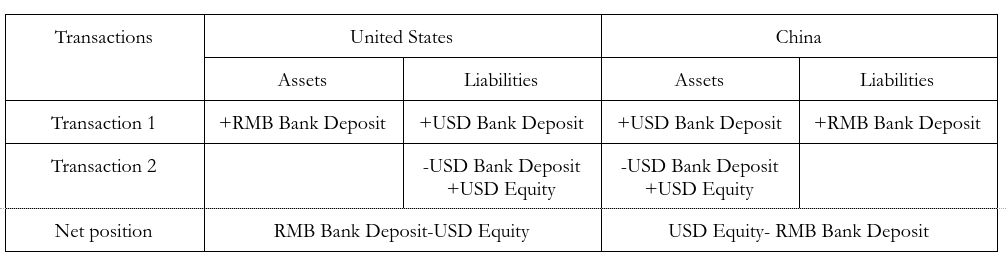

In transaction 1, the U.S. Bank now holds a Renminbi bank deposit and thus is a creditor of a Chinese bank. Meanwhile the U.S. Bank is now a debtor to a Chinese resident. The second transaction simply involves the Chinese resident purchasing a stock on the New York Stock Exchange. The final net position comes down to the United States owning a Renminbi bank deposit and “owing” a NYSE listed stock “to China”. The flipside of that is that “China” owes a Renminbi bank deposit and owns a NYSE listed stock.

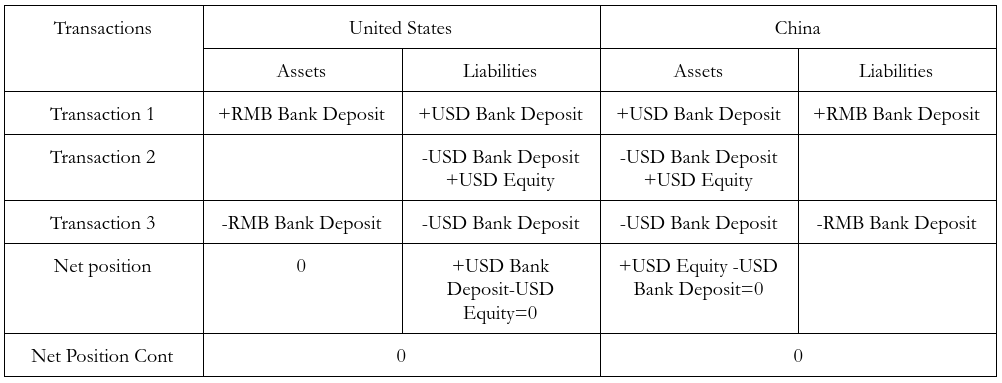

Since, as Pettis says, the current account surplus equals the capital account deficit, this is equivalent to the United States “investing” in a Renminbi Bank Deposit and “disinvesting” in a NYSE listed stock. It is also equivalent to China “investing” in a NYSE listed stock and “disinvesting” in a Renminbi bank deposit. To get to my fundamental argument though, we have to reduce the net positions down to a single number. To do that, we have to abstract away from a complication.

The final net position, as presented here, is reliant on current account transactions but also valuation changes. In other words, the exchange rate changing or the value of those equities changing will change the final net position. However, generally current account transactions and measures of current account balances don’t include valuation changes. That would be captured by changes in the “Net International Investment Position” which adds together net valuation changes and the current account balance. Pettis’s argument doesn’t rely on these valuation changes and he explicitly says he’s trying to eliminate the trade deficit without affecting the exchange rate greatly. As Pettis says:

Among other things, such a tax would not require huge shifts in the value of the dollar because it focuses so effectively on the most damaging kinds of capital inflows

To simplify and remove this valuation complication, let’s add a 3rd transaction step:

What jumps out here is that this crossborder financial transaction where notionally some Chinese resident is “investing their savings” in the United States has no effect on the current account position at all! Accommodating this portfolio decision doesn’t actually require net payments between countries, but simply the interfacing between both countries's banking systems. This is the fundamental reason that I’m skeptical of Michael Pettis’s narrative. Crossborder financial transactions which aren’t simply one-sided payments of dividends, interest or trade invoices don’t increase or decrease Current account deficits. When we talk about gross crossborder financial transactions, an increase in “capital inflows” simultaneously means an increase in “capital outflows”. Of course, a big upsurge in portfolio liquidations for the local currency and then sales of the local currency on the foreign exchange market can have a negative impact in the local currency’s exchange rate, but the transactions themselves don’t have any net effect on current account positions. Volatile financial flows tend to change current accounts through revaluing existing payments and disrupting future trade flows. These more indirect mechanisms are not what Pettis is referring to.

Of course, gross crossborder financial transactions can be related to crossborder payments. For example, a bank loan from one country can finance spending in another country which leads to the purchase of imports and a reduced trade balance. But Pettis’s recommendation isn’t based on reducing demand growth in the United States. If it was, he would spend time in his proposal talking about demand growth and talking about how the United States “spends too much”. Instead, his argument is that excess saving in current account surplus countries is lowering saving rates elsewhere:

Americans automatically tend to assume that it must be the United States that sets the savings schedule of the whole world, but this is unlikely. The high savings rates of countries like China, Germany, and Japan are too obviously a function of the distribution of domestic income (see here and here for why), making it far more likely that excess savings in those countries drive down savings elsewhere.

From my point of view, this confuses the propensity to spend and invest in these countries with saving rates. These countries do have high propensities to save and low propensities to invest out of income, but it is high net export growth (i.e. trade surplus growth) which is driving the rise of their incomes that finances those high saving rates. Other countries can have private sectors with high propensities to save but without high income growth (or even income growth at all) those propensities won’t translate into large quantities of saving. Further, the sectoral balances accounting identity tells us that these measurable current account surpluses must be translating into some combination of smaller budget deficits or larger private surpluses

Current Account Balance + Government Budget Balance= Private Sector Balance

In other words, rather than “excess saving in those countries driving down savings elsewhere”, its import spending growth in the United States outpacing import spending growth in these countries which drives the gap between them. The high propensity to save in these countries matters, but so does their successful export oriented growth model. Taxing crossborder financial transactions simply encourages those who receive payments in dollars and have no immediate purchase needs to sell their dollars on foreign exchange markets, potentially reducing the USD exchange rate. This is reinforced by discouraging foreign residents from entering into gross crossborder financial transactions in order to purchase U.S. assets. The dividend, interest and import payments will still need to be made but instead of occuring at current exchange rates, the reduction in foreign purchasers of U.S. assets will increase exchange rate volatility.

The other major way that gross crossborder financial transactions can lead to large net payments between countries is by contractually requiring future interest and dividend payments that are not matched by interest and dividend payments from foreign residents to domestic residents. This mechanism was first highlighted by the well-known economist Evsey Domar in a paper from 70 years ago entitled “The Effect of Foreign Investment on the Balance of Payments”. Since then, it's become known as the “Domar Effect”. This can be because domestic investments are more lucrative than foreign investments or because domestic actors are holding safer, low yielding foreign assets (like treasury securities). The local country can also simply not have comprobable foreign assets because of its trade deficit. But this doesn’t mean the gross crossborder financial transactions are causing the net imports. Outside of direct financing of import purchases, these flows tend to be unrelated. It’s only at the macroeconomic level that we can speak of trade deficits being “financed” by gross crossborder financial transactions. It is a fallacy of division to claim that because, at the macroeconomic level, gross inflows make it possible to net import without serious exchange rate depreciation that gross inflows are causing the net imports. Cutting off gross inflows may not reduce the trade deficit at all, especially relative to GDP.

Even if we accept the premise that a financing freeze would eliminate the trade deficit, it would not be because other countries “decided to save less”. Instead income growth in net-export oriented countries would fall, or even collapse, because import spending growth reversed itself in the United States. It would not be the painless adjustment that Pettis’s document suggests. It can’t be emphasized enough that Pettis is not focused on reducing spending growth in the United States, which is a required mechanism for all these possibilities to reduce the trade deficit. Further, at a certain point when spending growth in the U.S. reverses and countries with high propensities to save react to their lost income, we would come close to a global recession. It certainly would make the current lack of demand far worse.

The best case scenario for this tax closing the current account deficit without exchange rate volatility or a global recession is one that Pettis explicitly doesn’t argue for. The tax is designed to be avoided, on the theory that less “capital inflows” will reduce the trade deficit rather than simply reducing “capital outflows”. If, instead, net payments to foreigners are reduced because this tax straightforwardly reduces after tax payments to foreigners, it will reduce the overall current account deficit even if it doesn’t reduce the trade deficit. However, it’s not clear what the purpose of doing this is besides being punitive to foreign investors. Despite the U.S.’s large negative Net International Investment Position, the U.S. still earns far more on foreign investments than foreigners earn on U.S. investments. As we discussed, for other countries large crossborder financial flows can lead to big net payments to foreigners over time, but the United States does not have this problem at all. Meanwhile, the potential exchange rate benefits from reducing current account deficits are more than offset by discouraging and disrupting acquisition of U.S. assets by foreigners.

None of this means that regulating crossborder financial flows is a bad idea. However, this is not a good way to do so and the motivation is, in my view, severely conceptually flawed. Meanwhile, reducing spending growth in the United States by the degree it would require to very substantially reduce trade deficits would require a global recession. The United States supports the spending growth, and thus the income growth of the world. It’s not clear that the alternatives to that system that are currently on offer are much better.

Sign up for Notes on the Crises

Currently: Comprehensive coverage of the Trump-Musk Payments Crisis of 2025